The Middle Kingdom and Its War against Religion: A Historical Perspective

When speaking to military students at Nankai University in 2013, Chinese professor Ai Yuejin said the following: “Do you know what the foundation for our nation to become stronger is? It is not our national defence, not education, and not the economy. It is the vast territory we own…During the past 200 years, we have assimilated all of the ethnic minority groups in the peripheries of China into our race. The nature of our culture is to assimilate. We change and accept the good races into our own society and torture and eradicate the bad ones.” This essentially sums up China's long-standing historical and contemporary behaviours as well as its expansionism through the eradication of foreign cultures to annexe their regions.

From a historical perspective, today’s China is the legacy or result of the Sino-barbarian “struggle” characterized as (華 Hua) for Chinese and (夷Yi) for barbarians. Elimination of “barbarians” has been the key to achieving “Grand Unity” under the heavens. The official name of the People’s Republic of China (中华人民共和国 Zhong Hua Ren Min Gong He Guo) reflects the continuation of that prehistoric legacy.

According to Ai Yuejin's conclusion, the Middle Kingdom's survival has always been viewed as being threatened by differences; hence China's lengthy history has never been a tolerant place for the cohabitation of other races, ethnicities, or religions. Without this historical context, we only pay attention to symptoms that are visible on the surface and disregard the Middle Kingdom's concealed agenda. Anyone who is not Chinese is a "barbarian," and anything that is not from Chinese culture is from "foreign culture," both of which need to be eradicated unless thoroughly integrated. It is not by accident that the Uyghurs' fundamental religious and ethnic identities are the target of the current genocidal campaign.

Religious Demography

There are more than 200 million religious adherents in China, according to the State Council Information Office (SCIO) report ‘Seeking Happiness for People: 70 Years of Progress on Human Rights in China’ which was released in September 2019. There are reportedly about 5,500 religious groups in the nation, according to a white paper on religion published by SCIO in April 2018. Uncertainty exists regarding local and regional statistics regarding the number of adherents, including those from the five officially recognised religions (Protestantism, Islam, Catholicism, Daoism, and Buddhism). Even official religious organisations lack up-to-date statistics, as local governments do not release them.

According to Boston University’s 2020 World Religion Database, there are 499 million folk and ethnic religionists (34 per cent), 474 million agnostics (33 per cent), 228 million Buddhists (16 per cent), 106 million Christians (7.4 per cent), 100 million atheists (7 per cent), 23.7 million Muslims (1.7per cent), and other religions adherents who together constitute less than per cent of the population, including 5.9 million Taoists, 1.8 million Confucians, 20,500 Sikhs, and 2,900 Jews.

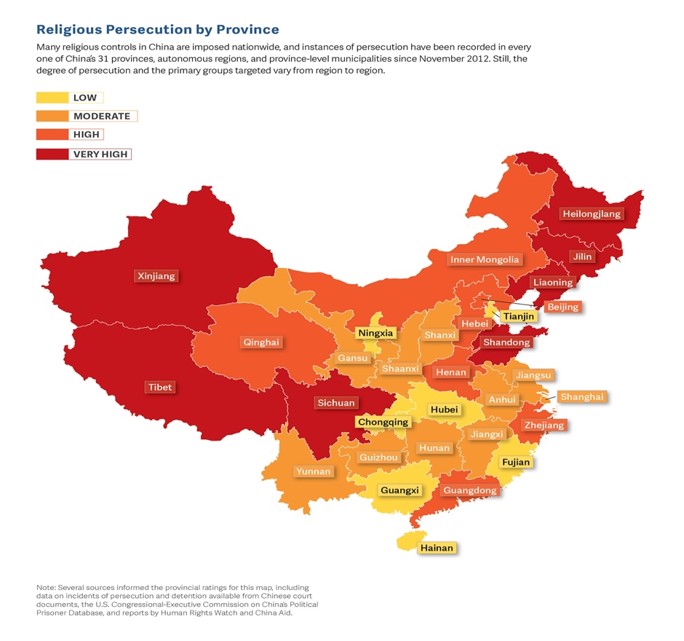

To maximise the benefits of party rule while minimising the risks, CCP leaders have pursued a complex policy, as they have come to terms with religion's persistence and the apparent growth in Chinese society. Four key pillars of the strategy are evident in its implementation. Firstly, they harness the benefits of religion to advance broader CCP economic, political, cultural, and foreign policy goals. Secondly, they develop legal and bureaucratic instruments to control religious practices and institutions. Thirdly, they fiercely suppress the religious groups, beliefs, and individuals deemed to threaten party rule or policy priorities, often via extra-legal means. Lastly, the party adopts measures to curb religion’s expansion and accelerate its extinction among future generations.

Freedom and Regulation

The Chinese constitution's Article 36 states that all people "enjoy the freedom of religious belief." It prohibits discrimination based on religion and bars state agencies, non-profits, or private persons from pressuring residents to adhere to a certain faith. State-registered religious organisations can now own property, print literature, appoint clergy, and collect donations according to legislation on religious affairs that the government's administrative body, the State Council, passed in February 2018. However, these liberties also come with more intrusive government regulations. The updated regulations limit the hours and places of religious festivals, regulate the online religious activity, and require reporting of gifts that surpass 100,000 Yuan (about $15,900).

The constitution in China protects religious belief, but according to Sophie Richardson, director of Human Rights Watch in China, the measures "do not guarantee the right to practise or worship." Religious practices are restricted to "normal religious activity," albeit the term "normal" is kept vague and open to many interpretations. The five religions that are recognised by the state are Protestantism, Islam, Catholicism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Although sometimes permitted, the practice of any other religion is officially outlawed, particularly when it comes to traditional Chinese beliefs. Religious organisations must register with one of the five state-approved patriotic religious associations, which are overseen by the State Administration for Religious Affairs (SARA).

Chinese public security officials monitor both registered and unregistered religious groups to prevent activities that “disrupt public order, impair the health of citizens or interfere with the educational system of the State,” as stipulated by the Chinese constitution. Human rights watchdogs claim that in reality, monitoring and crackdowns frequently target peaceful activities that are protected by international law. Overall, “religious groups have been swept up in a broader tightening of CCP control over civil society and an increasingly anti-Western ideological bent under [Chinese President] Xi Jinping,” writes Freedom House.

Under Xi, the CCP has pushed for the Sinicization of religion, or the reshaping of all religions to fit the official atheist party's tenets and the traditions of the predominately Han Chinese population. New regulations enacted in early 2020 require religious organisations to accept and spread CCP ideology and values. Before engaging in any activities, religious organisations must now obtain approval from the government's religious affairs office.

Furthermore, China has one of the largest populations of religious prisoners, likely numbering in the tens of thousands; rights groups claim that some are tortured or killed while detained. Since 1999, the United States State Department has designated China as a country of particular concern for religious freedom due to arbitrary detentions and impunity.

Chinese Buddhism and Folk Religions

According to Freedom House, China has the largest population of Buddhists in the world, with between 185 and 250 million adherents. Despite having its roots in India, Buddhism has a long history and tradition in China, where it is now the most widely practised institutionalised religion. Separately, according to a 2012 Pew Research Center study, more than 294 million Chinese people, or 21% of the country's population, practise folk religions. The worship of ancestors, spirits or other regional deities is a manifestation of Chinese folk religions, which combine practises from Buddhism and Daoism and lack a rigid organisational structure. The growth of Buddhism and folk beliefs in China is indicated by the construction of new temples and the restoration of older temples, although it is difficult to estimate the precise number of traditional Chinese religious adherents.

According to journalist Barbara Demick, former Beijing bureau chief for the Los Angeles Times, "Buddhism, Daoism, and other folk religions are seen as the most authentically Chinese religions and there is much more tolerance of these traditional religions than there is of Islam or Christianity." "Hundreds, if not thousands," of folk religious temples are tolerated, according to Ian Johnson, author of ‘The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao’.

The party has been tolerant of and tacitly approved of the rise in Buddhist practice since China's opening and reform in the 1980s. Although political winds can change quickly in China, Karrie Koesel, author of Religion and Authoritarianism: Cooperation, Conflict, and the Consequences, asserts that "having a positive, collaborative relationship with the government is important to these religious communities." According to Andre Laliberte of the University of Ottawa, under former Chinese leaders Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, the government "passively supported" the growth of Buddhism because it thought doing so helped enhance the perception of China's peaceful rise, supported the CCP's goal of creating a "harmonious society," and could help to improve relations with Taiwan.

Buddhism's expansion increased awareness of its institutions, particularly Buddhist charitable groups that provide aid to the underprivileged in the face of rising inequality in China. Experts have noticed an apparent easing of harsh rhetoric against, and even promotion of, traditional beliefs in China since Xi took office. Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism are considered to be China's "traditional cultures," and Xi has expressed the hope that they can slow down the nation's "moral decline."

Tibetan Buddhism

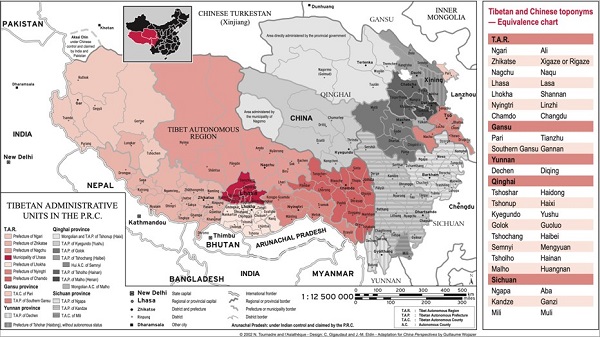

More than six million ethnic Tibetans live in the Tibet Autonomous Region and its neighbouring provinces, the majority of whom follow a particular branch of Buddhism. One of the main branches of Tibetan Buddhism is led by the Dalai Lama as its spiritual head. He and his exiled administration in India have been instrumental in gaining support for Tibetan autonomy on a global scale since 1987. Tibetan Buddhist monks have also taken part in largely nonviolent anti-government protests, though some of them have included riots and self-immolations. According to experts, economic inequality between ethnic Tibetans and Han Chinese as well as political and religious repression, are some of the causes of discontent among Tibetan Buddhists. A large number of Han Chinese have migrated to Tibet as part of a larger Chinese campaign to integrate its western regions.

Twentieth century Chinese regimes, including the Chinese Communists, have interpreted the history of the Tang- Tibetan relationship, particularly two marriage alliances between Tibetan kings and Chinese princesses, as evidence that Tibet began the process of becoming a part of China at that time. In 1248 Tibet was incorporated into the Mongol Empire, which at that time did not include China.

The British invasion of Tibet in 1904 was an attempt to keep Russia at bay and protect their Indian empire. But the British attempted to preserve for themselves a role in Tibet, particularly a commercial role, by means of their recognition of Tibetan autonomy under Chinese “suzerainty.” "Nominal sovereignty over a semi-independent or internally autonomous state" was the British definition of suzerainty. However, they were unable to convince the Chinese to accept Tibetan autonomy or limit their ambitions in Tibet to the British concept of suzerainty. The British were also unable to offer Tibetan autonomy any substance.

After the nationalist revolution of 1911 the Republican government attempted to retain all the territory of the Qing Empire by redefining the non-Chinese peoples of the frontier as part of the "five races" of peoples that shared Chinese heritage. The "five races," as defined by Sun Yat-sen, were the Han, Tibetans, Mongols, Manchu and "Tatars" or Turks (Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kirghiz, etc.). Sun Yat-sen's nationality policy was continued under the Kuomintang regime by Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang believed that Tibet had begun a natural process of assimilation to China in the seventh century.

The PRC adopted a system of “national regional autonomy” instead of a federal system as in the Soviet Union. The CCP claimed that none of China’s national minorities were in exclusive possession of contiguous territories free of other minorities or Han Chinese. The 1951 “17-Point Agreement for the Peaceful Liberation of Tibet” promised Tibet many more autonomous rights than were prescribed in the system of national regional autonomy. The 1957 retrenchment policy in Tibet was not a Chinese recognition of the legitimacy of or the need for Tibetan autonomy. It was a tool to suppress dissent in the region which failed to prevent revolt in eastern Tibet, which later spread to central Tibet and culminated in the revolt in Lhasa in March 1959. After the Tibetan revolt, China abolished the Tibetan government and abrogated the promises of the 17-Point Agreement. Tibetans' freedoms were severely curtailed by the repression of the revolt and the subsequent institution of "democratic reforms" during which Tibet's traditional leadership and institutions were substantially eradicated.

The ethno-religious status of Tibetan Buddhists is inextricably linked to China's approach to religion in Tibet. The CCP limits religious activity in Tibet and Tibetan communities outside of the autonomous region to quell dissent. The state imposes restrictions on lay Tibetan Buddhists, including those who work for the government and teachers, and also monitors daily operations at major monasteries with facial recognition cameras stationed outside. The state also reserves the right to reject a person's application to join a religious order. For instance, in 2018, Larung Gar, one of the biggest Buddhist study centres in the world, was placed under the control of party cadres and officials. Up to 6,000 monks and nuns were forced to leave the centre when authorities demolished nearly half of it in 2019.

Buddhists in Tibet are subjected to severe religious persecution. According to reports, the Dalai Lama has been ordered to be replaced in photographs by Chinese leaders, and monks and nuns have reportedly been imprisoned and tortured for refusing to denounce him. The Panchen Lama, a Tibetan child who is thought to be a high-ranking reincarnated religious figure, vanished in 1995 and hasn't been seen since. Beijing asserts that he has a job, a college degree, and prefers not to be bothered. Although many Tibetans reject him as the Panchen Lama, the government has named another child as the official Panchen Lama.

Christian State-Sanctioned and Horse Churches

Christianity has significantly increased in China since the 1980s, and today Protestantism is the nation's fastest-growing religious movement. In addition to numerous underground house churches of widely varying sizes, there are three state-regulated Christian organisations. Sixty-seven million Christians, or about 5% of the population, were estimated to be Christians in China in 2010 by the Pew Research Center. Of these, fifty-eight million belonged to the Protestant faith and were members of both state-approved and unaffiliated churches. According to some estimates, this number has risen to close to 100 million, with unregistered churchgoers outnumbering members of recognised churches by a ratio of almost two to one. The estimate of the Beijing-based Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, which counts twenty-nine million Christians, is significantly lower.

China has seen an increase in state repression against house churches and state-approved Christian groups in recent years. Examples include campaigns to remove hundreds of rooftop crosses from churches, forced church demolitions, and harassment and incarceration of Christian clergy. Religious persecution, particularly against Christians, was reportedly on the rise in 2018, according to a report from the Christian nongovernmental organisation China Aid, which has its headquarters in Texas. In 2018, the report cited more than a million instances of religious discrimination. Over a thousand church leaders were among the more than 5,000 people detained. Pastor Wang Yi, the founder of a sizable underground church and one of China's most well-known Christian figures, was given a nine-year prison term in 2019 after being found guilty of subverting state authority and engaging in illegal business practices.

Since 1951, the Vatican has not maintained diplomatic relations with China, which is home to between ten and twelve million Catholics. The main points of contention have been its recognition of Taiwan and an argument over the appointment of bishops. Pope Francis, however, recognised several Chinese state-appointed bishops who had been excommunicated as part of a provisional agreement between the two sides in 2018, which may be a sign of thawing relations.

Islam and Uyghurs in Xinjiang

Muslims make up about 1.7 per cent of China’s population, accounting for around twenty-four million people. There are ten ethnic groups that are primarily Muslim in China, the largest of which is the Hui. The Hui are a closely related ethnic group to the majority Han people and are mainly found in western China's Ningxia Autonomous Region and the provinces of Gansu, Qinghai, and Yunnan.

The Turkic Uyghurs, who are mainly found in the autonomous region of Xinjiang in northwest China, are mainly Muslim. Uyghurs make up about half of the population in this area, numbering about eleven million. In contrast to Muslims in the rest of the country, who typically enjoy greater religious freedom, authorities in Xinjiang strictly regulate religious activity. Hui Muslims in northwest China, however, have recently been subjected to a rise in repression, which has included the imprisonment of religious leaders and the forced closure of mosques.

Chinese authorities have been repressing Uyghurs in Xinjiang for decades on the grounds that the ethnic group harbours extremist and separatist ideologies. They cite sporadic acts of violence in the area against civilians and government employees, and they have accused the separatist East Turkestan Islamic Movement—founded by armed Uyghurs—of being responsible for a number of terrorist attacks across China. The majority of Uyghurs, according to experts, do not support the violence, but many of them are frustrated by frequent discrimination and the Han Chinese population's influx into the area, which is causing them to unfairly benefit from economic opportunities.

The repression has gotten worse recently. Experts and foreign government officials estimate that since 2017, up to two million Muslims, the majority of whom are Uyghurs, have been arbitrarily detained in so-called re-education camps. Detainees have complained of being sexually assaulted, tortured, denied access to their religion, and coerced into swearing allegiance to the CCP. According to a 2019 U.S. government report, many children of detainees are sent to boarding schools where they learn Mandarin and CCP ideology. Uyghurs are forced to undergo forced sterilisations, widespread religious restrictions, and intense surveillance outside of detention facilities.

Human rights violations in the area are denied by Chinese officials. They contend that the re-education camps serve two purposes: to teach citizens Mandarin, Chinese laws, and practical skills, as well as to shield them from extremist ideologies. Beijing has defied demands from other countries to permit unrestricted access for foreign investigators to Xinjiang.

Banned Religious Groups

Beijing refers to a number of religious and spiritual organisations as "heterodox cults," and the government frequently cracks down on them. More than a dozen such religions have been outlawed by the party-state on the grounds that their followers use religion "as a camouflage, deifying their leading members, recruiting and controlling their members, and deceiving people by moulding and spreading superstitious ideas, and endangering society." The Church of Almighty God, also known as Eastern Lightning, and Falun Gong, a spiritual movement that combines elements of Buddhism, Daoism, and conventional qigong exercise, are two of the quasi-Christian organisations that have been outlawed. Such classifications have been contested by international human rights organisations, religious scholars, and Chinese human rights attorneys who have criticised the Chinese government for harsh persecution of believers.

In 1999, a crackdown on Falun Gong was initiated following the organisation of a sizable, nonviolent rally outside the CCP headquarters to demand the release of detained adherents and more freedom to practise. Despite nearly two decades of persecution, Freedom House estimates that seven to twenty million people still practise the religion, which was once thought to have up to seventy million followers at its peak. Following a fatal attack on a woman in a McDonald's by alleged Church of Almighty God members, the Chinese government launched new campaigns against other smaller religious groups.

Evolving Mechanisms of Religious Control and Persecution

Despite the diversity of the Chinese government’s approaches to the management of different faiths, certain methods of control are evident across multiple religious groups. Four dimensions of the party-state’s apparatus—and their recent evolution—are particularly notable for their profound impact on the lives of ordinary people in China and the insight they provide into how the Chinese authorities interact with believers.

The Chinese state is expanding control over religious leaders and places of worship. There are indications the party-state is taking matters into its own hands and eschewing the assistance of religious intermediaries. It is common practice to send party cadres, Religious Affairs Bureau representatives, or security personnel to oversee Tibetan monasteries, explain party doctrine from church pulpits, and keep a close eye on anyone entering Uighur or even Hui mosques. Who is a "certified" reincarnated lama has been confirmed by a new government-run database. Additionally, the BAC's upper levels are increasingly staffed with former government employees.

The CCP employs to reform thought is by manipulating doctrines and re-educating religious groups. A Theological Construction Movement among Protestant Christians has focussed on undermining the traditional concept of "justification by faith," which has led Chinese Protestants to prioritise party-state authority over religious authority. A decade-long effort by Muslims to interpret Sharia and determine sermon topics has resulted in a number of leaflets that are distributed to state-approved ‘imams’ nationwide. And a new Uighur translation of the Quran reportedly contains updates that emphasise devotion to the state. A project started in 2011, has reinterpreted Tibetan Buddhist doctrines, producing pamphlets that reportedly required reading in monasteries.

The punishments meted out to religious leaders and adherents who evade or reject official restrictions are some of the harshest for any type of dissent in China. A state-approved church's Christian pastor was given a 14-year prison term for speaking out against the province's cross-removal campaign. A Uighur teen who viewed a religious video on his smart-phone was given a 15-year prison sentence as punishment. A senior Tibetan monk was sentenced to 18 years in prison after police raided his monastery and discovered pictures and audio recordings of the Dalai Lama. Additionally, a Falun Gong practitioner who displayed banners with the words "truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance are good" in them was sentenced to 12 years in prison. Other benign expressions of religious faith or dissent that have drawn long prison sentences since Xi Jinping took power in November 2012 include disseminating leaflets, praying in public, opposing the demolition of a place of worship, and growing a beard.

Lastly, there is evidence that suggests that extrajudicial executions of religious prisoners have taken place in order to supply organs for China's booming organ transplant market. Numerous inferential evidence, professional evaluations, and eyewitness accounts, in particular, point to the victimisation of Falun Gong practitioners. Even though the number of legal executions is declining and the number of willing donors is still extremely low, there are still many transplants carried out with little waiting time. In this context, reports of routine blood testing of Uighur political prisoners, the widespread disappearance of young Uighur men, and the unexplained deaths of Tibetans and Uighurs while in custody should raise concerns that these populations may also be the targets of organ harvesting.

Works Cited

- Carrico, K. (2017, June 13). China’s Cult of Stability Is Killing Tibetans. Retrieved from The Foreign Policy : https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/06/13/self-immolation-and-chinas-state-cult-of-stability-tibet-monks-dalai-lama/

- China’s Money and Migrants Pour Into Tibet. (2010, July 25). Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/07/25/world/asia/25tibet.html

- Gray. (2023, January 17). China’s Race Problem: How Beijing Represses Minorities. Retrieved from Foreign Affairs: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/china/chinas-race-problem

- China urges Tibetans to marry Chinese. Tibetan critics call it colonization. (2014, August 16). Retrieved from Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/asia_pacific/china-promotes-mixed-marriages-in-tibet-as-way-to-achieve-unity/2014/08/16/94409ca6-238e-11e4-86ca-6f03cbd15c1a_story.html

- Albert, E. (2018, October 11). Christianity in China. Retrieved from Counil on Foreign Relations : https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/christianity-china

(2011). Global Christianity. PewResearch Center. - Rahn, W. (2019, January 19). China's crackdown on Christianity. Retrieved from DW: https://www.dw.com/en/in-xi-we-trust-is-china-cracking-down-on-christianity/a-42224752

- (2018). Chinese Government Persecution of Churches and Christians in Mainland China. ChinaAid.

- China Sentences Wang Yi, Christian Pastor, to 9 Years in Prison. (2020, January 2). Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/30/world/asia/china-wang-yi-christian-sentence.html

- China and Vatican Reach Deal on Appointment of Bishops. (2020, October 22). Retrieved from The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2018/09/22/world/asia/china-vatican-bishops.html

- The harsh reality of China’s Muslim divide. (2012, October 12). Retrieved from AlJazeera: https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2012/10/12/the-harsh-reality-of-chinas-muslim-divide/

- Feng, E. (2019, September 26). 'Afraid We Will Become The Next Xinjiang': China's Hui Muslims Face Crackdown. Retrieved from npr: https://www.npr.org/2019/09/26/763356996/afraid-we-will-become-the-next-xinjiang-chinas-hui-muslims-face-crackdown

- Maizland, L. (2022, September 22). China’s Repression of Uyghurs in Xinjiang. Retrieved from Council on Foreign Relations : https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/china-xinjiang-uyghurs-muslims-repression-genocide-human-rights

- The Xinjiang Papers . (n.d.). (The New York Times ) Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/11/16/world/asia/china-xinjiang-documents.html

- (n.d.). 2019 Report on International Religious Freedom: China (Includes Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Macau). OFFICE OF INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM.

- China cuts Uighur births with IUDs, abortion, sterilization. (2020, June 29). Retrieved from AP News : https://apnews.com/article/ap-top-news-international-news-weekend-reads-china-health-269b3de1af34e17c1941a514f78d764c

- Religion in China. (2020, September 15). Retrieved from Council on Foreign Relations: https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/religion-china

- (2022). 2021 Report on International Religious Freedom: China (Includes Tibet, Xinjiang, Hong Kong, and Macau). US Department of State.

(n.d.). The Battle for China’s Spirit. Freedom House. - Alana. (2015). This fascinating map shows the new religious breakdown in China. Retrieved from Business Insider: https://www.businessinsider.in/home/this-fascinating-map-shows-the-new-religious-breakdown-in-china/articleshow/48643425.cms

Post new comment