The 28th meeting of Conference of Parties (COP 28) of UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC) is being convened in Dubai from 30th Nov to 12 Dec 2023. The meeting is being held in the backdrop of IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (SAR), which states that the world is “way off track” from keeping the global warming within 1.5 ̊C, a goal that was set at Paris COP 26 in 2015. All eyes are now on COP 28 to see whether the much needed course correction to keep the emission to a manageable level will happen.

The global climate situation is truly grim. It has been estimated that the year 2023 has been the hottest in the last 1,25,000 years. CO2 levels in atmosphere have reached 413 ppm. Scores of extreme weather events ranging from forest fires to floods and devastating cyclones have been seen in different parts of the world. The window of opportunity for controlling the runaway warming of the planet is closing rapidly. According to a UN report, 1.5 ̊C temperature level was breached 86 times in 2023.

The UAE presidency of the COP 28 is pushing for “four paradigm shifts” namely, significant reduction in green house emissions through “equitable and orderly energy transition” before 2030; a new deal on climate finance; bringing livelihood concerns to the heart of climate action and ensuring inclusivity in the COP process. In a letter addressed to participants of COP 28, Dr Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, President designate of the COP 28 underlined several priorities. Some of these are:-

- Cutting down 22 Gigatons of GHG emissions by 2030 to keep global warming within 1.5 ̊C.

- Tripling of global renewable energy capacity to 11 Terawatts (TW) by 2030.

- Doubling energy efficiency by 2030.

- Decarbonisation of heavy emitting and energy sector by setting strong 2030 target.

- Revised, more ambitious Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) by states.

- Enhanced climate action finance for developing countries with greater focus on grants and concessional finance.

- Setting up “better international finance institutions” fit for meeting the climate and developmental needs of developing countries.

- New finance for resilience, adaptation and prevention of loss and damage with focus on nature, food, water and health.

- Inclusion of women, indigenous people, youth, and faith based organisations in climate processes.

A World Climate Action Summit (WCAS) will be held during COP 28 to take stock of the present climate situation. The leaders will formally conclude the first global stocktaking of climate actions, mandated by the 2015 Paris Agreement.

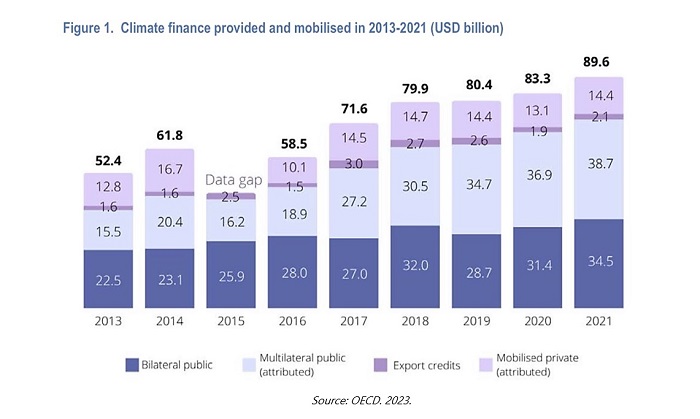

These are laudable objectives but given the record of previous COPs, it is difficult to be too optimistic. Climate negotiations are ultimately about politics. COP 28 is taking place in the backdrop of complex geopolitics characterised by polarisation and fragmentation. Finance is at the heart of climate action. On this front, the developed countries have failed miserably. Even the USD 100 bn per annum of climate finance that was promised by the developed countries to the developing counties in 2010 has not been forthcoming although there is a claim by the OECD that this figure was achieved in 2023. One cannot be too sure of the methodology adopted by the OECD in calculating the climate financial flows. The crucial point is on theterms and conditions on which USD 100 bn funds will be provided. Further loans will only add to the indebtedness of the already debt stressed countries. The concessional finance on grants are the need of the hour.

A lot of hope is placed on renewable energy (solar and wind) as the panacea for reducing emissions. The present day reality is that renewable energy systems are financially not viable for many countries. The cost of energy transition to renewable energy has been vastly understated. Renewable energy has its own downside. For stable supply of electricity, solar and wind power generation needs to be augmented with vast storage capacity and transformed energy transmission systems. This adds to the cost of renewable energy and also to its carbon footprint.

Renewable energy technologies are mostly owned by the companies of developed countries. Energy transition is likely to benefit these companies significantly. For most countries, dependencies on fossil fuels are going to be replaced by the dependencies for renewable energy technologies which are available only with the developed countries.

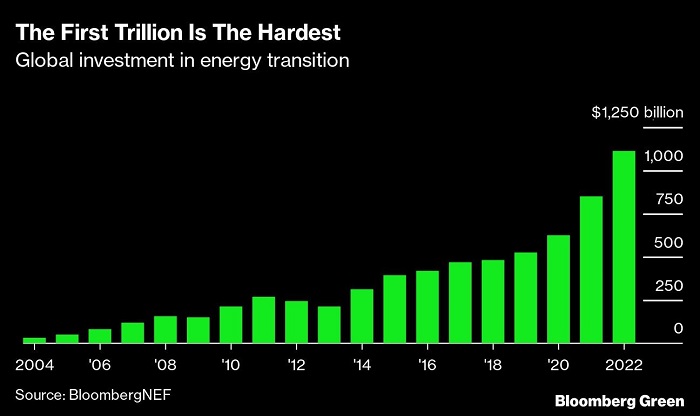

We have also seen how fragile the commitment to renewable energy even among the developed countries is. Soon after the Russia-Ukraine war and the disruption of natural gas supplies from Russia to Europe, European countries scrambled to the Middle-East for import of oil and LNG to meet their energy needs. In some countries, thermal power plants, which had been closed, were restarted. Nuclear energy, which had been dismissed as dangerous and unsafe, came into fashion again. Fossil fuels companies are talking about renewable energy but are also making new investments in fossil fuels. Although investments in renewables is increasing, those in fossil fuels continue to remain robust. In 2023, out of a total investment of USD 2.8 trillion in energy, about 40 percent was in fossil fuels. These are long-term investments. We are also seeing that global coal production and consumption is at record levels. China and India account for about two-third of global coal consumption.

India

India has a difficult balancing act to perform. On the one hand, it needs more energy to fuel growth; on the other hand it must undertake an energy transition to net zero by 2070. Energy transition is going to prove expensive. This is not going to change significantly in the near future.

At COP 26 at Glasgow, India declared five targets and goals:

- To achieve the target of net zero emissions by 2070.

- To reduce the emissions intensity of GDP by 45% by 2030 from 2005 level.

- To achieve about 50% cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel based energy resources by 2030.

- To have 500 GW non-fossil energy capacities by 2030.

- To reduce the total projected carbon emissions by one billion tonnes by 2030.

India has an impressive record on climate change. Our per capita emission is much below that of China, EU or US. Per capita GHG emission for India in 2020 was 2.4 ton of CO2 equivalent as compare to global average of 6.3 ton; 14 tons for USA, 9.7 tons for China, 7.2 tons for the EU (please see annexure). We need not be defensive on this score. We have to communicate our viewpoint more effectively at the official platform as well as to the global media and public opinion. According to the Union Minister RK Singh, India has achieved its NDC target of 40% of our installed electricity capacity coming from non-fossil energy sources nine years ahead of schedule, in 2021 itself. “Today, 43% of our capacity is from non-fossil fuel sources. No other country has added renewable energy capacity at a rate at which we have done. We pledged at COP-21 in 2015, that we will reduce our emissions intensity by 33% by 2030; we did this by 2022, eight years in advance. So, in Glasgow, we have said that by 2030, we will have 50% of our capacity coming from renewables and that we will reduce our emission intensity by 45%. We will achieve that too well before time.”

Still, India needs more carbon space to grow. It cannot ignore its developmental needs. While India has been a trendsetter in climate change discussions, it cannot ignore the imperatives of energy security i.e. access to affordable energy at all times to all its citizens.

Indian economy is growing at 6 to 7 percent per annum and needs to grow even faster to overcome poverty and afford a reasonable standard and living for its vas population. Having been a late starter, it cannot accept unreasonable restrictions on energy use at this stage of its growth trajectory. Our transition to renewable energy will have to take into account own needs and priorities.

VIF Report

The Vivekananda International Foundation recently published a report of a group of experts in which it made several recommendations. Titled Climate Change: Reflections on Issues, Challenges and the Way Forward, the report notes that India is committed to be a part of the solution to the climate change and lists several positive steps taken by India. It makes the important recommendation that India must treat the remaining carbon budget as a “strategic national resource” and ensure that it has fair share of the remaining carbon budget in the coming decades. An artificial deadline for peaking should be avoided.

India’s share in the global carbon space is only 4 percent while it accounts for a fifth of humanity. India has to ensure that it claims a proportional share of the remaining carbon budget (about 250 Giga tons) in the next few years. India cannot afford early peaking on the use of fossil fuels. We must be careful in deciding about the peaking year and avoid being pressurised in this regard.

Developed countries are raising the issue of methane emissions. Agriculture is crucial for India’s survival. India should be careful about the methane reduction plan (30 percent by 2030 from 2020 levels) being propagated by the US and other countries. It is imperative that India distinguishes between ‘survival emission’ and ‘luxury emission’ of methane.

Meat based diets and consumption oriented lifestyles carry heavy carbon footprint. Indian lifestyles are frugal and have low carbon footprint. Prime Minister Modi has emphasised the need for change in lifestyle for durable solution to climate change problems. This was taken up at the G20 summit as well. It is necessary that India should spread Lifestyle for Environment (LiFE) mission at the global level.

Globally, a pressure is building for decarbonisation of energy intensive sectors like steel, aluminium, fertiliser etc. India should ensure that its industry does not become uncompetitive due to aggressive lobbying in this regard. It is imperative that a level playing field is created for all industries.

Adaptation is the neglected child in climate change negotiation. India should ensure that a suitable climate adaptation fund which is accessible to vulnerably countries is created.

The VIF report suggests that India’s approach at COP 28 should be guided by the principle of ‘climate justice’ and equity. Regrettably, discussions and negotiation at COP pay only lip service to these principles and tend to become too legal and technical. Geopolitics takes over negotiation at some point. India, in its negotiation approach, should continue to insist upon the principles of Common but Differentiated Responsibility (CBDR). India’s diplomatic approach at the COP 28 negotiation should be guided by the following considerations:-

- Climate change problem was not created by India. Yet India is willing to be a part of the solution. India should insist upon climate justice and equality.

- India should present its record on climate change effectively.

- India should seek to change the climate change narrative from total emission to per capita emissions.

- India should resist pressure from western countries on methane, coal phase down, early peaking, carbon tax, decarbonisation etc.

- India should lobby for enhanced climate finance, greater share of grants and concessional loans, reforms of MDBs, loss and damage based on a country’s vulnerabilities, MDB reforms etc.

- India should strengthen international solar alliance and Coalition for Disaster Resilience Initiative (CDRI).

- India should insist on phasing down of all fossil fuels and not just coal.

One hopes that COP 28 would prove to be truly a landmark event. India should play an active role in these negotiations.

Annexure

-

Diplomatic position.

- USA: It believes that every country has a responsibility to tackle climate change. It wanted developing countries like China and India to do more.

- Reducing emissions by 50-52% by2030.

- Reaching 100% carbon pollution-free electricity by 2030.

- Achieving a net-zero emissions by 2050.

- EU: It believes that every country has a responsibility to tackle climate change. Wanted developing countries like China and India to do more.

- Reducing emissions by 55% by 2030 and becoming the first climate-neutral continent by 2050.

- China: It considers itself a developing country and demands the same considerations to be given to it.

- Achieving peak carbon emissions by 2030.

- Achieving a net-zero emissions by 2060.

- Small Island Developing States (SIDS): It demands climate justice based on the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC). It believed that developed countries should do more as they are disproportionately responsible for climate change.

- They insist vehemently on the 1.5°C warming limit.

- They demand payment for loss and damage and climate financing for adaptation.

- India: It demand climate justice based on the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC). It believed that developed countries should do more as they are disproportionately responsible for climate change.

- It demands climate financing and technology transfers for clean energy transition and adaptation.

- Reduce emissions intensity of its GDP by 45% by 2030 from 2005 level.

- Achieve about 50% cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030.

- Achieving a net-zero emissions by 2070.

-

Global targets on emissions reductions.

- To keep global warming to no more than 1.5°C - as called for in the Paris Agreement - emissions need to be reduced by 45% by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050.

- This target remain in place. However, existing policies are far from delivering on it.

-

CO2 concentrations.

- Greenhouse gas concentrations hit record high again in 2022.

- Global averaged concentrations of CO2, the most important greenhouse gas; in 2022 is 36.6 billion tonnes (50% above the pre-industrial era) for the first time. The last time the Earth experienced a comparable concentration of CO2 was 3-5 million years ago.

- Carbon budget: According to a recent analysis, carbon budget remaining for a 50% chance of keeping global temperature rise below 1.5°C is about 250 billion tonnes. The new figure is half the size of the budget estimated in 2020 and would be exhausted in six years at current levels of emissions.

- Global emissions are expected to reach a record high this year of about 40 billion tonnes.

-

Emissions trend.

- Global energy-related CO2 emissions grew by 0.9% or 321 million metric tonnes in 2022.

- US emissions increased by 0.8%.

- EU’s emissions declined by 2.5%.

- China’s emissions declined by 0.2%.

- India’s emissions increased by around 6%.

-

Energy investments.

- Clean energy: Clean energy investment totalled USD 1.1 trillion in 2022. That could increase to around USD 2.8 trillion in 2023.

- Coal: Investment in coal was USD 135 billion in 2022. That could rise 10% in 2023 to USD 150 billion.

- Oil and gas: Investment in oil and gas increased by 39% in 2022 to USD 499 billion.

-

Warming levels – current and future projection.

- Current global average temperature for the most recent decade, 2013 to 2022, was 1.14°C. It was 1.07°C between 2010 and 2019.

- But existing national pledges to cut emissions will lead to 3°C of warming.

- To still have a chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, 22 billion tonnes of CO2 must be cut from the currently projected total in 2030. That is 42% of global emissions and equivalent to the output of the world’s top five emitters: China, US, India, Russia and Japan.

-

Per capita GHG emissions (including land use, land-use change, and forestry – LULUCF) as of 2020.

- USA - 14 tCO2e (tonne carbon dioxide equivalent).

- Russian Federation - 13 tCO2e.

- China - (9.7 tCO2e).

- Brazil & Indonesia - 7.5 tCO2e.

- EU - 7.2 tCO2e).

- India - 2.4 tCO2e.

- World average - 6.3 tCO2e.

-

Historical cumulative CO2 emissions (excluding LULUCF) from 1850 to 2019.

- US - 25%.

- EU - 17%.

- China - 13%.

- Russian Federation - 7%.

- India - 3%.

- Indonesia & Brazil - 1%.

-

Climate finance.

- In 2009, developed countries pledged to mobilize USD 100 billion annually from 2020 and onwards. But this target has not been met.

- At COP28, governments will continue their negotiations on a new climate finance goal to replace the USD 100 billion commitment.

-

Loss & Damage.

- At the moment, the Loss & Damage fund is an empty pot of money. It will take several years until money was allocated to it. As such, it will continue to remain at the top of the global climate agenda.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://articles.unesco.org/sites/default/files/2023-10/cop28logo.jpeg

Post new comment