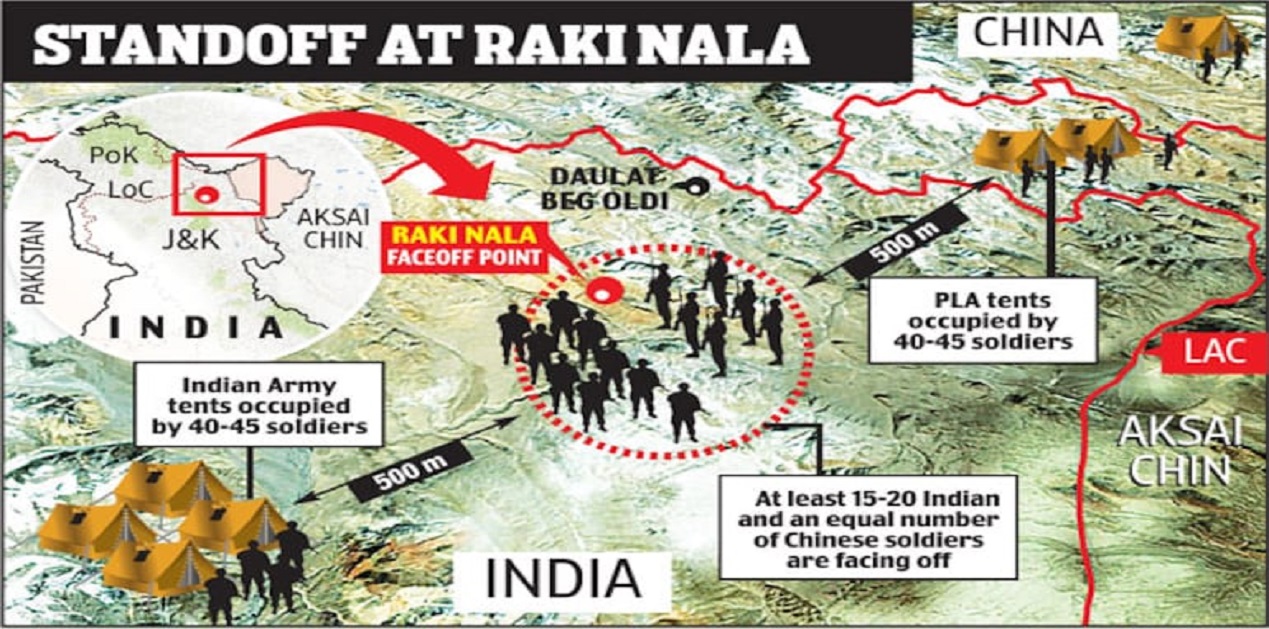

In mid-April of 2013, with Xi Jinping regime in saddle, the PLA set up a camp nearly 19 kilometres west of the Line of Actual Control (LAC) near the Raki Nala in India’s strategically sensitive Depsang Plains part of Eastern Ladakh. The intrusion came to the countrymen’s notice after some ten days, and that led to much consternation among the people and their representatives in the Parliament, besides, of course, our active television media.

As was its wont, the Indian Government acted maturely. The intrusion was forcefully blocked without engaging in any hostile action. The Government then made statements aimed at playing down what actually was a brazen affront and so kept China in good humour.1 There were no hard diplomatic exchanges, strong protests or chastising the ambassador. Rather, the incident was described as a ‘local matter’ and an inconsequential ‘acne on a beautiful face’, to be resolved by beseeching China’s benediction. With an apparent show of magnanimity, China then decided to let India off in return for an apparently ‘token’ tribute in the form of removal some of our bunkers in South-Eastern Ladakh (Chumar). A border crisis was thus averted after three weeks of bargaining and barricading.

The Chinese Way

As distinct from the usual patrolling practice, the Raki Nala incident offered a palpable indication of China’s impending enforcement of its arbitrary territorial decrees. Those familiar with China’s methods of military-diplomatic policy making and enforcement would know that the idea of deliberate intrusion-in-force into this area would have been mooted some years back. The location would have been selected after due military appreciation of China’s long-term strategic goals and approved at the Party-CMC level and clinched on the strength of certain parameters: One, easy approachability over a motorable plateau-land; two, mostly obstacle or bottleneck free ground between the PLA base at Sogma (Qizil Zilga) and the intrusion camp situated 25 kilometres apart; three, availability of water from the shallow Raki Nallah; four, domination over a sensitive part of India’s under construction road alignment -Bursa Gongma Gorge-Depsang Plains -to connect Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO) to Leh; and five, the location being out at a limb from Indian bases. Preparations would have begun a few years back in order to build up military capability in that kind of remote and hostile terra-firma of wind swept cold desert situated at an average height of 4500 metres.

Once the plan had been approved at the highest level of the Chinese hierarchy, advance preparations would have begun in anticipation of the executive order to carry out the intrusion. Preparations would have included build-up of logistic infrastructure to support at least one division level operation including base installations, and development of operational tracks and advance landing grounds close to the LAC. All that, even by China’s pace of engineering, would have taken a year or more to be in place. These activities could not have been hidden from sharp eyes and ears.

One visualises that while the final activities associated with the intrusion were being executed some months back, most firm base level construction works would have been nearly completed – some semi-permanent, some of permanent nature - probably near Sogma on the Western Highway. Stocking of supplies, spares and ammunition at this base would also have been completed. Besides, some of the existing cross-country alignments of vehicular tracks would have been strengthened by gravel compaction. At this juncture, a regiment level PLA force would also be in location, duly equipped, acclimatised, trained and rehearsed to ‘counter-attack in self-defence’ against any ‘provocative offensive’ that could purportedly be unleashed by the ‘stubborn’ Indians. More forces at a state of battle readiness would be placed on short notice to deploy from their bases in the hinterland Tibet as well from the adjoining Military Region. Lastly, indignant propaganda with farcical show of injured innocence would have been scripted and kept ready to be unleashed if the matters escalated. And then, finally, the intrusion would have been executed.

Following up, preparations would be readied to consolidate the intrusion; a camp would be set up, road from the base at Sogma would be developed, pre-fabricated huts and ancillary structures would be ready to be on their way and provisions would be ready to be stocked up. There would be a smart looking flag pole flying the People’s Republic of China flag, but apart from few well insulated sentry posts, there would be no defences constructed; PLA knew that Indians were in no position to force an eviction, neither was it possible to cut-off the camp in that flat, ‘go anywhere’ terrain.

In all probability, all these developments on the Chinese side would have been suspected in the Indian defence establishment, but overlooked in hope that China would not escalate matters to the extent it actually did.

Launch of Intrusion

China’s timing was perfect. The Indian Government, seized in domestic politicking, was hard put to stay on the course of economic developments; it had little time to look at border security concerns. China’s military modernisation was well poised, the new Chinese leadership had firmed-in and ‘provocations’ from Japan and other neighbours on territorial matters were becoming irritating enough to be responded through a show of power against a fairly strong neighbour. Besides, India’s road building into the ever-vulnerable Eastern Ladakh had reached an advanced stage of completion, and that could be a concern against the Chinese strategists’ plans to push the LAC westwards. Finally, even as the Chinese do not take measures by the half and would have deployed overwhelming forces in depth locations, they could also appreciate that India might not be in a position to react with force.

In the event, as distinct from the practice of the contesting border patrols showing their flags at points of intrusion across India’s well-articulated and physically dominated alignment of the LAC, this one was part of a deliberately conceived, planned, executed and well supported operation. Even if India did confront the intrusion, and the Chinese wound up their camp, but then a swath of territory beyond the Raki Nala - as in many previously encroached areas - has become out of bounds to Indian border patrols.

Having assumed the usurped territory, the Communist regime’s Middle Kingdom would not backtrack; rather it will use it as a firm base for subsequent encroachments. The forewarning was loud and clear, but the Government continued with its standard bet that “There will be no war with China.”

A Trailer

Notwithstanding our successive Government’s adopted – albeit reluctant - practice of overlooking China’s arbitrary enforcement of its territorial claims, this incident offered an indication of future developments, ominous in content and dangerous in fallouts.

On the ground, as stated, a long standing limit of own forces’ patrolling up to the LAC stood pushed some kilometres to the West, and to that extent own control over a swath of Indian territory was more or less lost. Perhaps the incident ended with what was the best possible resolution under the circumstances, particularly in light of the fact that India, standing alone against China, could not hope to evict the intrusion without provoking a war, and when India’s ability to seek any kind of international support rested upon her power of appeal, and little else. Nothing, including deft diplomacy, works if it is not founded on an ability to wield formidable political-military-economic power.

Fallouts of Neighbourly Arrogance

By its sustained disorientation from national security, our successive governments have placed the nation in this helpless situation. It is certain that this situation has been brought as a matter of deliberate policy, for the governments had been informed of such vulnerabilities many times in the past. In such occasions, the government’s response had been, “There will be no war with China”; a true, if sad, statement because in any case, India would not be in a position to fight, no matter what the provocation might be.

Successive Indian Government’s lower prioritisation of the dangers shaping up from an arrogant, aggressive neighbour’s rising belligerence on the pretext of focussing on socio-economic investments has placed us in a precarious situation. For any political resolution of the territorial issue to have a chance, the Communist regime has to be convinced that its adoption of military option will not succeed. Conversely, it would take India many years to marshal a strong, fully balanced force and consolidate the attendant logistics to dam Communist China’s territorial expansion. Even then it would be a back-foot fight for us, albeit a thoroughly chastising one for the PLA and the Chinese regime’s eccentric ambitions.

That is the price we must pay for continuing to play music to the Chinese ears when Indians were being issued with ‘stapled’ visa, or when Prime Minister’s visit to Arunachal Pradesh was being objected to, or when a road development work well inside India was stopped at the PLA’s finger wagging, or when Indian spokespersons played down China’s 500 odd annual LAC violations, or when China does not even indicate as to what her ‘perceived’ LAC might be, or when China sets up village astride the desolate McMahon Line-LAC ...... the list of China’s brazen conduct is not exhaustive.

Vulnerability of the LAC

Before proceeding further, let us see as to what makes India’s territorial security so vulnerable along the Indo-Tibet border.

In Eastern Ladakh, first we may consider the situation that prevails in its Northern Part – the Sub-Sector North. The area is North of the Pangong Tso where lies the strategic Depsang Plains (5400 meters) and the small garrison of Daulat Beg Oldi (DBO). With just two seasonal mule tracks, this Sub-Sector is poorly connected with the rest of Ladakh. Helicopters on hover and the old, now reconstructed airfield at DBO are the alternate means for air connectivity. A 224 km road along the Eastern alignment is under construction. Presently, vehicles can negotiate, with some difficulty, over the formation cut for this road, whereas it would take some years for the road to meet the designated military classification.

In rest of Ladakh, road connectivity is better, though afflicted with seasonal snow cover and hazardous alignments which keep these non-commercial for a good part of the year. Work is ongoing to stretch the usability of these roads.

In the North-East, road connectivity from Western Arunachal Pradesh right up to the Myanmar Tri-Junction along the McMahon Line requires major upgrades. The works are going on while there has been some improvement in air connectivity.

It is obvious that without robust lines of communications, it would not be wise for India to undertake deliberate military operations before being able to build up a fully balanced and logistically maintained force, with more ready at the jumping board should matters escalate. It will take India some years to marshal that kind of capability and that would include necessary upgrades to the many tenuous in-depth lines of communications. Meanwhile, if it comes to that, the Indian military remains adequately prepared for a military confrontation; it would be an uneven fight, albeit a rather chastening one for the PLA.

In Sum

Lessons be learnt. After Raki Nala, followed by Chumbi Valley in 2017 and the current confrontation in Eastern Ladakh, it should be expected that in the coming days there would be no let-up in China’s recurrent territorial grab. May be in time, some kind of mutual ‘give-and-take’ – which in China’s parlance means her ‘take-and-take’ - might be arrived at that would stop further loss of territory for the time being. But the Chinese regime’s culture would not allow her to give up on predation upon neighbours. We have to prepare for that eventuality.

Endnotes

- The incident was described as a ‘local matter’ and an inconsequential ‘acne on a beautiful face’, to be resolved without hard diplomatic exchanges, protests or chastising the ambassador. The show of humility or submission – describe as you like - was accompanied with sentiments of injured dismay over the Chinese targeting an accommodative peacenik friend that India was.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://akm-img-a-in.tosshub.com/indiatoday/images/story/201304/26fir17_660_042613091721.jpg?size=770:433

Post new comment