Introduction

Due to lack of an internationally accepted definition, terrorism continues to haunt every nation in the World. The perspective of terrorism differs from a nation to nation; therefore, every country has its own definition and measure to counter terrorism. De-radicalisation and counter-terrorism are two inter-linked terms that are widely used in studies related to extremism, terrorism, and radicalisation. Most of the accessible work or literature on the subjects are linked with Islamist-inspired extremism or terrorism. In radicalisation, it is important to understand the victim or an individual who is radicalised but, also there is a need to analyse the role of the organisation and their capabilities for radicalisation. Over the matters related to terrorism, radicalisation, or extremism, the international cooperation seems to be incomplete due to the absence of internationally-accepted definition of terrorism, and a ‘pure’ intention to contain this common evil. To fill the gap, there is a need of States to come together on shared platform and effectively engage in their policies of de-radicalisation to counter the radicalisation process of the terrorist organisations. This paper introduces its reader with the Counter-Terrorism framework of the United Nations and various elements of radicalisation and de-radicalisation process. In later part, the paper highlights India’s successful approach to counter radicalisation through its different programmes.

Radicalisation and its Stages

Post-September 11 terrorist attack, the European Commission coined a term to research on a new part of terrorism—‘Violent Radicalisation’. The narrative of ‘homegrown terrorism’ which emerged post Madrid attacks in March 2004, and London suicide bombings in July 2005, blamed the immigrant Muslim community in the country, especially the case of the UK. The US-invasion of Iraq on the terms of ‘War on Terror’ had angered many Muslims around the world and gave them an excuse to join the terrorist organisations to fight against Western ‘oppressors’. The US and EU made a curve of its research on extreme Islamist ideology interfering with the Muslim youth in Western countries in the form of radicalisation, and some drivers behind it with the involvement of certain Mosques, and prison spots.2 Radicalisation can be viewed as a ‘conversion process’— a life changing transformation within an individual to make him obedient to the extremist-religious group.3

The ‘Pull’ and ‘Push’ factors at micro-level plays an important role in radicalisation and de-radicalisation process. In the process of radicalisation poor economic conditions of a country is insufficient to turn a common-man into a terrorist. However, in his article on ‘root cause of terrorism’, Edward Newman suggested that there is always a link between terrorism, social-economic, political, and demographic conditions.4 The lack of control by any government on its economic conditions would provide an opportunity for transnational terrorist organisations to firm their base and gather massive support.5

Another important aspect in radicalisation process, which is ignored during research on radicalisation and de-radicalisation, is an individual who is assigned to radicalise the potential recruits. Termed as ‘radical preachers’, such individuals do not indulge themselves directly in the violence, but through their charisma, they encourage others “to do” or “to contribute” more for their cause. The global presence and anonymity offered by the Internet have ensured the virtual presence of such preachers to be remain ever.

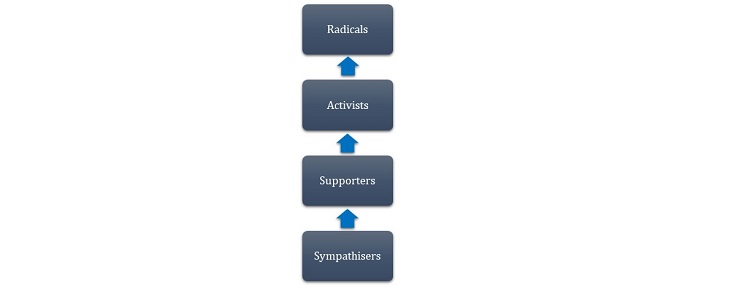

Figure 1 shows bottom-to-top stages through which an individual’s transforms to a radicalised extremist or terrorist. The figure is based on the ‘pyramid model of radicalisation’ developed by two psychologists— Clark McCauley, and Sophia Moskalenko, conceptualising ‘political radicalisation’ as change in beliefs, and actions for the good of the group.7 It begins with an individual being Sympathiser who agree to the cause but do not submit to the violent means. The group of sympathisers agree with the goals, mostly political, of terrorist organisation. These are the ‘non-official’ representatives of the terrorist ideologies living within the civic society. At second stage, sympathiser transforms into being Supporter who not only agree with the ideology but also justifies the stand of terrorist organisations for their violent actions. From this stage, the mindset to take risks for the cause started developing. Third level of radicalisation comes with an individual who becomes an Activist who yet not engage themselves in violent actions but provide logistic support to the terrorists. As a final product of the process, it is a Radical extremist who is highly committed to the cause, willing to take risks, and engages in violent actions for the cause. The numbers of radicals are comparatively less than the numbers of sympathisers. However, radicals turned extremists gained more media attention through their violent actions. The silent but real threat is posed by the sympathisers who at later stages becomes radicals.

De-Radicalisation and its Approach

De-radicalisation can be defined as the process in which tools and techniques are engaged to challenge and reverse the completed radicalisation process with an individual or group. The measures of de-radicalisation reduce the risk factor to the civic society from terrorism. Most of the time, de-radicalisation term is confused with ‘counter-radicalisation’, and ‘anti-radicalisation’. However, these terms are inter-linked but different in their nature. Counter-radicalisation can be understood as the measures taken to stop or control the on-going radicalisation process, whereas anti-radicalisation is a process to deter and prevent radicalisation from occurring at the first instance. 8

Family and kinships do play important role in the process of both, radicalisation and de-radicalisation. In radicalisation, it is notable to see how the terrorist group managed to get brothers from the same family or distinct relatives to join their respective groups. For example, one of the perpetrators of the Sri Lanka’s Easter Day bombings in April 2019, Zahran Hashim had his brother Rilwan Hashim to build the explosives alongside another member of the terror group.9 Another example, in June 2016, a group of 22 people, including four couple travelled from Kerala to Afghanistan via Iran, to join IS in Nangarhar province in Afghanistan.10

In the process of de-radicalisation, two approaches could be useful: i) bringing radicalised individuals back to the civic society, and ii) bringing them back to true faith. 11 The world is divided in two parts on this issue. In the western and most of the south-Asian countries, the first approach is implemented. Much focus has been given upon the return of a radicalised individual back to the mainstream. Whereas in the Middle-East countries, the emphasis is given on the return of an individual to true religion.

United Nations’ Counter-Terrorism Strategy

To define radicalisation in simple terms, it is a process in which an individual’s attention and ideology is been ‘hijacked’ with the associated factors over the time to make him or her a prospective recruit for terrorist organisations. During the process, an individual becomes highly motivated to use violent means to achieve goals, behavioural or political, by targeting an out-group or symbolic figures— political and non-political.12 On 08 September 2006, the United Nations (UN) has adopted a ‘Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy’ which is a unique instrument to enhance the national, regional, and international cooperation to counter terrorism.13 The strategy is not only the condemnation of terrorism and its manifestations, but also a mutually accepted agreement by all UN Member States to work on strategic and operational approach to combat terrorism. The ‘Plan of Action’ to combat terrorism was introduced in the form of Resolution: A/RES/60/288, under which the agencies would contribute to the implementation of the counter-terrorism strategy through the mandate and the membership of the United Nations Counter-Terrorism Implementation Task Force (CTITF). The task force consists of 38 agencies as international entities.

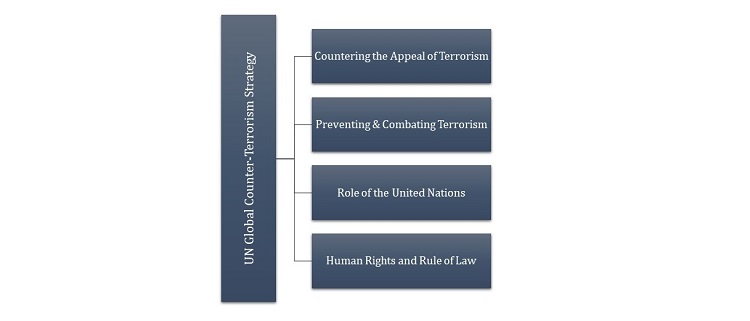

The UN’s Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy has four main aspects: i) Countering the appeal of terrorism; ii) Preventing and combating terrorism; iii) Role of the UN; and iv) Human Rights and Rule of Law:-14

- Countering the Appeal of Terrorism: The first aspect deals with implementing the strategy by countering the appeal of terrorism, the economic and social factors that plays a significant role in terrorism. This Plan of Action includes initiating the dialogue and understating among the Member States to promote economic and social development. In order to implement prevention and peaceful resolution to the unresolved conflicts, the UN recognises the use of its capacities such as conflict prevention, negotiation, judicial settlement, peacekeeping, and peacebuilding, which would contribute to strengthen a global fight against terrorism.15 The aspect also enforce the measure to promote the culture of peace, justice, and further human development. The initiatives on social development, especially on youth unemployment, could marginalise the sense of victimisation which fuels radicalisation, and recruitment to terrorist organisations at later stages.

- Preventing and Combating Terrorism: The second aspect of the ‘Plan of Action’ deals directly with the law-enforcement. It involves the activities of law-enforcement, Border control authorities, including the prevention and response to an attack. The strategy implies on the activities to combat financial terrorism, protection to the Critical Infrastructures (CI), Cyberspace, and vulnerable targets. In accordance to the international law, the strategy expects all Member States to fully cooperate in order to deny safe havens. On the basis of extradition laws, any individual who supports, facilitate, or attempts to participate in the financing, planning or preparation of any terrorist act, shall bring to justice. The aspect also signifies the coordination of efforts at the international and national level to combat terrorism in all forms and its manifestations, including on the Internet.16 The Internet shall be used to counter the propaganda of the terrorist organisations.

- Role of the United Nations: The third aspect signifies the importance of the United Nations (UN) to facilitate the cohesive implementation of the UN’s Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, and further develop the implementation of legal and international instruments, which includes providing legal support, and enrichment of the capacity of the officials of criminal justice and law-enforcement officers. The measures under the Plan of Action encourages the Member States to increase the frequency of meetings, frequent exchange of information on cooperation and technical assistance with other bodies of the United Nations dealing with counter-terrorism. It also emphasises on the role of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and the International Criminal Police Organisation (ICPO)/Interpol to improve the cooperation among the Member States to combat money-laundering and financing of terrorism.17

- Human Rights and Rule of Law: The fourth aspect deals with the protection of the victims of an act of terrorism through trainings facilitate to the law-enforcement official. This ensures the Human Rights protection, and rule of law, as a part of the support provided to the victims of terrorism. This aspect indorses the UN General Assembly Resolution 60/158 of 16 December 2005 which provides a framework considering the “protection of Human Rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism”.18 The UNSC had recognised that the military, intelligence, and law-enforcement operations would not be enough, but the protection of Human Rights and rule of law are also equally important to combat radicalisation and terrorism. The Human Rights grievances are among other factors which establishes the recruitment ground for terrorist organisations. The violations of basic Human Rights could act as a ‘trigger’ for an individual or family members to turn towards violence.19

On 01 February 2018, the UN Secretary-General, and other 36 UN institutions, including the UN Office of Counter-Terrorism (UNOCT), and the Interpol had agreed and signed ‘Global Counter-Terrorism Coordination Compact (GCTCC). The primary responsibility of GCTCC is to ensure the effective operation of UN’s Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, with fully coordination among GCTCC members. On the bright side, the resolution addresses the issue of returning Foreign (Terrorist) Fighters [FTFs] and emphasised on the requirement of developing the “rehabilitation and re-integration policies, irrespective of gender and age, for returning or relocating foreign terrorist fighters and their respective families.20 On contrary, the proposal of rehabilitation and re-integration of FTFs had faced opposite views from some of the Western politicians. The concerns were regarding the returning of the nationals of these respective countries who have travelled to Islamic State (IS) controlled territories in Iraq or Syria to join the terrorist organisation. In December 2017, British Defence Secretary— Gavin Williamson gave a controversial statement regarding returning FTFs, that “Britons who have fought for Islamic State abroad should be hunted down and killed to ensure they never return to the UK (United Kingdom).21 Opposite to UN’s policy on FTFs, another controversial statement had come from France’s Defence Minister Florence Parly. During an interview in October 2017, French Minister Parly had said that “we (France) are committed along with our allies to the destruction of Daesh (Islamic State) and we’re doing everything to that end. What we want is to go to the end of this combat and of course if jihadists die in the fighting, then I’d say it is for the best”.22

According to an assessment on FTF’s and returnees done by The Soufan Group in October 2017, an estimate of 1,910 French nationals travelled to IS-controlled territories in Iraq or Syria and joined IS. Out of 1,910, women and children count to 320 and 460 respectively. However, France had 302 returning FTFs.23 On one side if returning FTFs pose challenges and threat to the National Security, the other side of them returning brings an opportunity to ensure the justice for victims. According to Reed Brody, Human Rights Watch, there is a possibility to work with the returning FTFs to uncover the operational strategies of IS, including building the war-crime cases against high-ranking leaders of IS for their involvement in atrocities and brutality. 24 Focusing on strengthening the fourth aspect— Human Rights and Rule of Law, of UN’s Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, in June 2018, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres addressed the ‘High-Level Conference on Counter-Terrorism’. In his closing remarks, Secretary-General Guterres emphasised on the establishment of new unit in UNOCT— ‘Global Internet Forum to Counter Terrorism’ and the significant role of civil society organisations in counter-terrorism policies and programmes. The new unit would ensure the opinions from civil society organisations shall fully reflected in future policies to deal with terrorism and radicalisation.25

Apart from the UN, the policies to counter terrorism and radicalisation have been introduced at multifaceted platform. The European Union (EU) begun to enhance the intelligence and data sharing with an undertake of Counter-Extremism Project at both regional and international levels. Similarly, the United States (US) shifted its narrative from ‘Global War on Terror’ (GWoT) to ‘Counter Violent Extremism’ (CVE) providing an importance on building counter-narratives and working towards CVE.26

India’s De-Radicalisation Approach

India has been facing terrorism and aspects of radicalisation since 1970s at different levels, be it terrorism in Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), Punjab, Central India or North-Eastern States. Apart from the threat posed by Sri Lanka based terrorist organisation—LTTE (Liberation of Tamil Tigers Eelam), India has witnessed several incidents of terrorism, including infamous 2001 Indian Parliament attack, and 2008 Mumbai attack. Despite of terrorist threats, India has made an important contribution towards counter-terrorism at international platform. In 1996, India had proposed ‘Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism (CCIT) at the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) which intends to “criminalise all forms of international terrorism, denial of safe havens, access to funds, and arms to terrorists and the financiers of terrorism. Till 2016, the CCIT was in a ‘dead’ state because of difference in the opinions among the members States to define an act of terrorism, and the opposition from the US, the Organisation of Islamic Countries (OIC), and the Latin American nations. From CCIT, the US demanded the exclusion of the acts committed by its military forces during peacetime, the OIC expects exclusion of ‘national liberation movements, mainly of Israel-Palestine conflict. The CCIT also proposed all Member States to agree to make cross-border terrorism an extraditable offence globally27, and to amend their domestic laws to integrate with the proposal. India has not lost hope on CCIT and believe that framework against all forms of terrorism will be adopted be a significant initiative to make counter-terrorism a global phenomenon.

Monitoring the threat of radicalisation pose by transnational terrorist organisations, the Indian State of Uttar Pradesh’s Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS) has been running a program— ‘Home Coming’ which de-radicalises the youth inspired with IS ideology. The ATS of Maharashtra aired a social awareness video regarding the online radicalisation. The video showed a young aspiring student’s parents talking about their son’s success in studies and dedication to work on his personal computer during the extended hours, but later the video shows that the aspiring student was indulge in learning the making of a bomb from a tutorial on the Internet. In the later part of the video, the officials of ATS shows up to parents and tells them about their son’s extremist activities online. The video ends with a message given by an Indian celebrity, urging parents and friends to become responsible and keep alert about their children and friend’s online activities. 28

In mid-2016, Kerala police, along with other law-enforcement agencies had launched a ‘silent’ but a strategic preventive measure against the influence of IS among the youths in the State. The law-enforcement officials mined the social media for extremist content and prepared the list of 350 ‘vulnerable’ youths. In the result, ‘orthodox’ religious routine, the age (all of them were in their twenties), and their high academic background (many were pursuing engineering and medicine studies) were some of the common factors.29 At the preliminary stages of the programme, the officials approached community elders and parents, and organised the collective counselling sessions, handled by specially-trained officials from the India’s National Investigation Agency (NIA) and the Intelligence Bureau (IB). On quick response to the programme, many youths came on one platform of belief that ‘the route was not easy as it was shown to them by their handlers’. This de-radicalisation programme received full support from the community leaders, and families of the victims.30

With a desire to deal with problem of radicalisation, India has adopted the framework of Malaysia to modernise the Islamic education in India. Under the plan, Indian officials, not only from security agencies but also from Ministry of Human Resource Development and Ministry of Minority Affairs visited Kuala Lumpur to understand the procedure of modernisation of the religious studies.31 To contain the radicalisation of youth from the minority communities, India has adopted a plan to engage them in various sectors such as education, sports, urban planning, skill development, social justice, and health. However, such programmes which mainly focuses on the youths from minority communities, does signal that the minority communities in country are at risk of being radicalisation. To address the root cause of terrorism, and radicalisation, there is a need to empower the communities and civil societies through counter-narratives.32

Conclusion

Radicalisation is a process of different stages, through which an individual transform to become an extremist of terrorist. Where conventional methods, such as social networking at physical level and radical preaching at Madrasas are very much in existence, online radicalisation is a new tool of radicalisation but rare verifiable examples. 33 In the long-run, an individual who gets radicalise only does require social-interaction with its recruiter. Therefore, recruiters tend to begin the process of radicalisation through online contact, and later the process takes place in cities and neighbourhood where it is convenient to harden ideological positions.34 The advance stages of the technology, widespread access, and anonymity of the Internet has made social media platforms a fertile ground for terrorist organisations. The terror groups are not only utilising the Internet-enabled tools for communications, but also for the dissemination of their propaganda among their sympathisers without crossing any borders. Although radicalisation process is of multi-levels, having an individual at focus point, it is also essential to understand the socio-political milieu around the individual. For a successful de-radicalisation and counter-terrorism strategy, it is essential to design and implement with the collaboration from all stakeholders, including corporate, governments, non-government organisations, and communities, to build a platform with a common objective.

References:

- This paper was presented at the “International Seminar on Counterterrorism, De-Radicalisation, and Human Rights Protection”, held at Urumqi, Xinjiang Province in the People’s Republic of China, on 03-06 September 2019. The host of the conference— China Society for Human Rights Studies, has published the “Abstract” section of this paper on their website, and could be accessed from: http://www.chinahumanrights.org/html/Features/07/5/3/2019/0912/13817.html

- Alex P. Schmid, “Research on Radicalisation: Topics and Themes”, Perspectives on Terrorism Vol. 10, 3 (2016): 26-32, Available from: http://www.terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/viewFile/511/1011

- Ibid.

- Edward Newman, “Exploring the ‘Root Causes’ of Terrorism”, Studies in Conflict &Terrorism Vol. 29, 8 (2006): 749-772, Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10576100600704069

- Anurag Sharma, “The Islamic State Foreign Fighters Phenomenon and the Jihadi Threat to India”, MPhil thesis, Dublin City University, 2019. http://doras.dcu.ie/22558/1/Anurag_Sharma_MPhil_Thesis_FINAL.pdf

- Diego Muro, “What does Radicalisation Look Like? Four Visualisations of Socialisation into Violent Extremism”, University of St. Andrews & Barcelona Centre of International Studies, December 2016, Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311761712_What_does_Radicalisation_Look_Like_Four_Visualisations_of_Socialisation_into_Violent_Extremism_2016

- Clark McCauley, and Sophia Moskalenko. “Mechanisms of Political Radicalization: Pathways to Terrorism”, Terrorism and Political Violence, 20:3 (2008), pp. 415-433.

- Lindsay Clutterbuck, “Deradicalization Programs and Counterterrorism: A Perspective on the Challenges and Benefits”, Middle East Institute, Available from: https://www.mei.edu/sites/default/files/Clutterbuck.pdf

- Saeed Shah, and Spindle, Bill. “Blew up motorcycles, lost fingers: How Lanka bombers trained for the attack”, Business Standard, 06 May 2019, Available from: https://www.business-standard.com/article/international/blew-up-motorcycles-lost-fingers-how-lanka-bombers-trained-for-the-attack-119050600220_1.html

- PTI, “22 Missing Keralites have reached IS’ bastion in Afghanistan: NIA sources”, NDTV, 14 September 2016, Available from: http://www.ndtv.com/kerala-news/22-missing-keralites-have-reached-ISs-bastion-in-afghanistan-nia-sources-1458610

- Alex P. Schmid, “Research on Radicalisation: Topics and Themes”, Perspectives on Terrorism Vol. 10, 3 (2016): 26-32, Available from: http://www.terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/viewFile/511/1011

- Bertjan Doosje, Fathali M Moghaddam, Arie W Kruglanski, Arjan de Wolf, Liesbeth Mann, and Allard R Feddes. “Terrorism, radicalization and de-radicalization”, Current Opinion in Psychology no.11 (2016):79, Available from: https://nvvb.nl/media/cms_page_media/694/Terrorism%2C%20radicalization%20and%20de-radicalization.pdf

- “UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy”, United Nations, Available from: https://www.un.org/counterterrorism/ctitf/en/un-global-counter-terrorism-strategy

- Radhika Halder, Understanding Suicide Terrorism (India: K W Publishers Pvt Ltd, 2019), 215.

- “UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy”, United Nations, Available from: https://www.un.org/counterterrorism/ctitf/en/un-global-counter-terrorism-strategy#plan

- “UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy”, United Nations, Available from: https://www.un.org/counterterrorism/ctitf/en/un-global-counter-terrorism-strategy#plan

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Fionnuala Ni Aolain, and Martin Scheinin, “Centralizing Human Rights in the Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy”, Just Security, 16 March 2018, Available from: https://www.justsecurity.org/53583/centralizing-human-rights-global-counter-terrorism-strategy/

- Hanny Megally, “The UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy Reviewed: Raised expectation, missed opportunities from the June 2018 review”, Center on International Cooperation, 15 August 2018, Available from: https://cic.nyu.edu/publications/UN-Global-Counter-Terrorism-Strategy-Review

- Jessica Elgot, “British ISIS fighters should be hunted down and killed, says defence secretary”, The Guardian, 08 December 2017, Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2017/dec/07/british-isis-fighters-should-be-hunted-down-and-killed-says-defence-secretary-gavin-williamson

- AFP, “Wanted dead, not alive: France’s approach to French jihadists”, The Local, 18 October 2017, Available from: https://www.thelocal.fr/20171018/wanted-dead-not-alive-frances-approach-to-is-jihadists n

- Richard Barrett, “Beyond the Caliphate: Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees”, The Soufan Group, 31 October 2017, Available from: https://thesoufancenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Beyond-the-Caliphate-Foreign-Fighters-and-the-Threat-of-Returnees-TSC-Report-October-2017-v3.pdf

- Imogen Foulkes, “What should happen to IS fighters in Syria and Iraq?”, BBC News, 02 November 2017, Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-41818290

- United Nations Secretary General, “Secretary-General’s closing remarks at High-Level Conference on Counter-Terrorism”, The United Nations, 29 June 2018, Available from: https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/statement/2018-06-29/secretary-generals-closing-remarks-high-level-conference-counter

- Radhika Halder, Understanding Suicide Terrorism (India: K W Publishers Pvt Ltd, 2019), 216.

- “What is the Comprehensive Convention on International Terrorism?”, Live Mint, 28 September 2016, Available from: https://www.livemint.com/Politics/Ee84kLhbyP5NJ9mFnMzkKO/Will-Sushmas-speech-at-the-UNGA-give-fresh-push-to-antiter.html

- Anurag Sharma, “The Islamic State Foreign Fighters Phenomenon and the Jihadi Threat to India”, MPhil thesis, Dublin City University, 2019. http://doras.dcu.ie/22558/1/Anurag_Sharma_MPhil_Thesis_FINAL.pdf

- Zee Media Bureau, “How ‘operation pigeon’ helped Kerala police counsel 350 youth against joining ISIS”, Zee News, 30 June 2017, Available from: https://zeenews.india.com/kerala/how-operation-pigeon-helped-kerala-police-counsel-350-youth-against-joining-isis-2020033.html

- Ibid.

- Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury, “India approaches Malaysia for an anti-radicalisation Islamic education system”, The Economic Times, 26 July 2016, Available from: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/industry/services/education/india-approaches-malaysia-for-an-anti-radicalisation-islamic-education-system/articleshow/53388777.cms

- Radhika Halder, Understanding Suicide Terrorism (India: K W Publishers Pvt Ltd, 2019), 213.

- Sean C. Reynolds, “German Foreign Fighters in Syria and Iraq” (MA diss., Naval Postgraduate School, 2016), pg. 73, Available from: http://calhoun.nps.edu/handle/10945/48583

- Diego Muro, “What does Radicalisation Look Like? Four Visualisations of Socialisation into Violent Extremism”, University of St. Andrews & Barcelona Centre of International Studies, December 2016, Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311761712_What_does_Radicalisation_Look_Like_Four_Visualisations_of_Socialisation_into_Violent_Extremism_2016

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://www.radicalisationresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Radicalisation-balloon-1024x601.jpg

Post new comment