The Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) emerged as the largest party with 115 seats in the National Assembly, besides winning two-third seats in the Khyber Pakhtunkwa (KP) provincial assembly and emerging as the second largest party in the Punjab assembly with 123 seats, only six seats short of Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz’s (PML-N) 129 seats. In urban Sindh, the party dealt a massive blow to the Muttahida Qaumi Movement-Pakistan (MQM-P) and clinched 12 of Karachi’s 21 National Assembly seats, and is expected to form a coalition government in Balochistan. Both, Imran Khan and the PTI have come a long away especially in these ten years, beginning with the PTI’s boycott of the 2008 elections, followed by its relatively poor performance in the 2013 polls.

Almost twenty-two years after Imran Khan founded the PTI, the sea change is visible in the two eras when Imran lost on both National Assembly seats he contested on during the 1997 elections and his present victory on all five seats he contested on. For his admirers, the basis of Imran’s victory lies in his natural leadership traits, strong will and his ability to identify talent, that had also led the Pakistani cricket team to the world cup victory under his captaincy in 1992, and the subsequent establishment of the cancer hospital he had pledged.

In the present context, the PTI had some achievements to its credit in KP, where its first tenure did result in improvements in the healthcare, education sector, besides police reforms. Imran’s popularity wave was strong enough to overshadow even the big ticket infrastructure projects which came up in Punjab under Shahbaz Sahrif’s tenure and the China Pakistan Economic Corridor projects across Pakistan whose credit Nawaz Sharif had been claiming.

An overall understanding of Imran’s victory alludes to his gradual evolution from an emotional crusader to a pragmatic strategist who not only learnt to communicate with the masses, but also transformed his support into victory by employing a set of means which he described as “science of fighting elections”. Nevertheless, his personal conduct has not gone unquestioned.

Unlike the PML-N or Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP), which have relied on patronage-cum-ideologically driven mass support bases, the case is different for Imran as his supporters come from diverse backgrounds, ranging from the youth, to the aspirational urban middle class, the liberals as well as the conservative lot. While Imran’s westernized upbringing and allegations on his personal conduct (including a tell-all book by his former wife) were overlooked to an extent that it did not dent the PTI’s electoral performance, his support to the conservative parties has been very much open. He was credited with giving tickets to women in areas where no woman had even voted in decades. At the same time, his rendezvous with extremists, and his view that “feminism degrades motherhood” helped retain his popularity among the conservative sections.1

In 2014 his sympathy for the Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan made the group nominate him as one of its interlocutors with the Pakistani establishment although he backed out later2. Imran has been a staunch supporter of Khatm-e- Nabuwwat issue too. Also, immediately after the election results were declared, the PTI was quick to reach out to Muavia Azam (son of slain Sipah-e-Sahaba chief Azam Tariq) to solicit support from the newly elected Member of Punjab Assembly, where the party vies for the required numbers to form government.

Another trait of his that could provide fodder to the opposition parties is his tendency of U-turns that have also made him a subject of controversies from time to time. His newfound support to the Army, the decision to tactically back the PPP in the Senate elections and the decision to field “electables” despite their questionable backgrounds does not give any indication of him being different from the traditional parties which he accuses of being responsible for the state of Pakistan. Moreover, the PTI would need to tread cautiously as a strong opposition (which has questioned the fairness of the poll results) awaits it in the Parliament.

New Delhi too has its share of challenges. Over the years, as the PTI evolved into a mainstream party, Imran’s views on India have become aligned with the structural constraints that define the Indo-Pak relationship. His erstwhile personal admiration for India has given way to a political cynicism that he has used to win the Army’s support as well as target the Sharifs. Regarding his India policy, there had been apprehensions in past over his hawkish views which were later confirmed as PTI’s election campaign repeatedly targeted Prime Minister Modi, followed by Imran’s speech a day after the elections. Not only did he accuse India of portraying a negative image of him, but also indicated that peace and trade were conditional on the resolution the Kashmir issue. A few days before the elections, his meeting with Fazlur Rehman Khalil, an old figure in Kashmir’s Jihadi networks was another proof of how the new administration’s Kashmir policy might unfold. Imran has also equated Indian control over Kashmir as a forceful occupation and likened it to America’s invasion of Afghanistan.

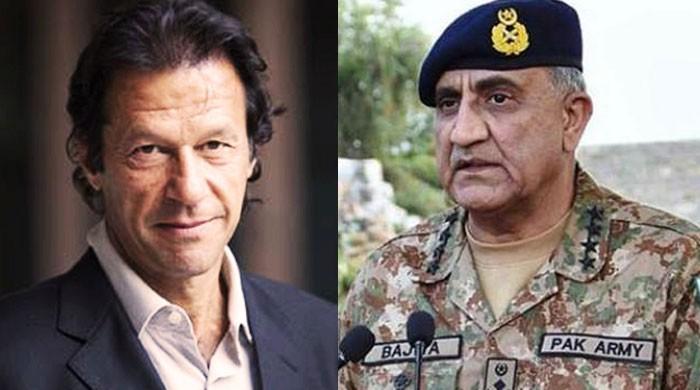

Here, he seems to have repeated the Pakistan Army’s line insinuating a possible surrender of the future government’s external affairs decision-making to the Army. Given his views, it is still too early to write him off as someone pandering to the military’s diktat, yet understanding his changing equations with the Army is indispensable as it would form the basis of the future government’s stability.

Some historical background is necessary if one is to analyse Imran’s relationship with the Army. According to his former captain Javed Miandad, Imran of the past seemed very apolitical who would shy away from political discussions and remained aloof. As his political views evolved, his disdain for the Army became visible when he would time and again accuse the Musharraf regime’s post-9/11 foreign policy as well as the Army’s role in propping up the civilian leadership. He termed the 2013 elections unfair citing an understanding between the Army and PML-N which ensured the latter’s victory, and named one former military intelligence official Brigadier Ranjha who supervised the job to ensure PML-N emerged as single largest party. 3

In another instance, while giving an interview to an Indian journalist, he went on record calling for establishing the supremacy of the civilian government over the military if he were to become the Prime Minister and added that he would prefer to resign if the military did not function under him.4 He emphasised bringing the ISI under civilian control and the audit of the defence budget. During 2013 election campaign, he even promised that he would order Pakistan Army to shoot US drones if they crossed into the Pakistani territory and insisted that the Army would be asked to withdraw from FATA where peace had returned and would bring in reforms to empower police and local government. However, the equation was to change once the Army’s discomfort with Nawaz’s became apparent.

In Najam Sethi’s words, what appears as of now is a tactical adjustment between the PTI and the Army, whereby a larger national party (accompanied by smaller regional parties and pressure group turned political parties) was needed to corner the PML-N.5 The natural choice was none other than Imran, whose hatred for Pakistan’s traditional civilian leadership, and the specifically the PML-N, knew no bounds, as it was demonstrated by the PTI’s four month long sit-in in 2014 after the Nawaz regime refused to investigate the instances of poll rigging. The phase also prepared grounds for the military to choose an alternative to the PML-N in case the leadership became too big for its shoes, which it eventually did. As Imran is likely to officially take charge as the Prime Minister on 11th of August, there are talks whether he would complete a full term or face similar fate as every prime minister has seen in the past. His relationship with the Army would need to be closely observed.

End Notes:

- Shailaja Neelakantan, “Pakistan's Imran Khan says 'feminism degrades role of mother'”, The Times of India, New Delhi, June 18, 2018.

- “Imran will not represent Taliban, says PTI”, Dawn, Islamabad, February 03, 2014.

- Zulqernain Tahir, “Ex-MI official rejects Imran’s claim of army help for PML-N”, Dawn, May 05, 2018.

- “Imran Khan says army, ISI will be kept under check”, Firstpost, November 11, 2011.

- Najam Sethi, “Welcome to “New” Pakistan!”, The Friday Times, July 26, 2018.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://khabarial.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%AC%D9%88%D9%87-%D8%A7%D9%88-%D8%B9%D9%85%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86.jpg

Post new comment