China Factor: A Seven Decades Old Dispute Debated on Packets of Information

In recent times - especially after the Galwan incident of 15 June 2020, Sino Indian border dispute is the most intensely debated topic in Indian media. The contents and the tone of media debates at times provide misleading perception due to digitised nature of information that forms the basis of debates in general. Views on the present Government’s capability to manage this dispute range from ‘excellent’ to ‘very poor’ grades. Recently the dispute was compared to Russia-Ukraine conflict with India playing Ukraine’s role. The internal debate looks at the entire issue as a pre and post 2014 subject- for obvious reasons. It is here that the popular discourse tends to pick up ‘discrete packets’ ignoring the continuity factor of the Sino Indian relations.

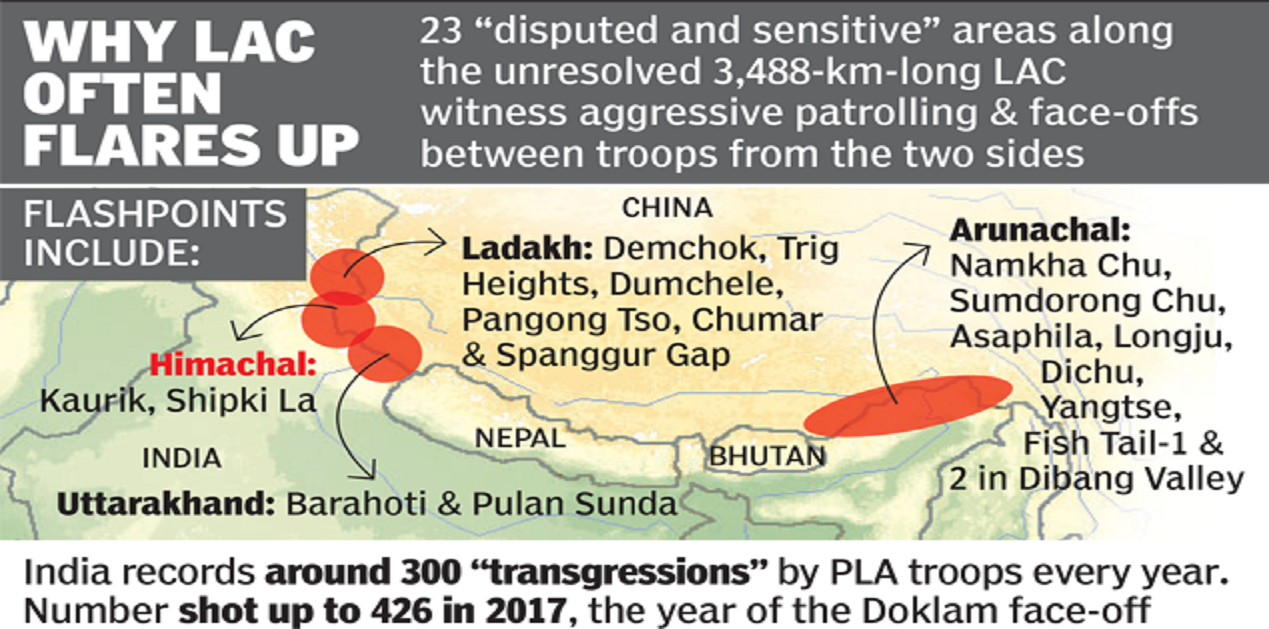

China became India’s immediate neighbour in 1951. There after relations between the two countries have generally been turbulent in spite of apparent efforts by the top leaderships of the two nations to for peaceful coexistence. The two countries share 3488 kms (in some publications this border is considered around 4000 kms long) of border[1]. Most of the border is disputed and hence it is common to refer to the Sino India border as Line of Actual Control (LAC). The LAC is divided into Northern, Central and the Eastern sectors.

There are three aspects that need to be analysed to arrive at a clearer picture of this complex kaleidoscope. First is to look at the popular ‘conflict events’ pre and post 2014 focusing on geopolitical posturing by the antagonists at the top political levels, actual military action on ground, impact on the conflict spectrum and subsequent preparations by the rivals. Secondly, analysis of these events in terms of shifts in India’s strategic approach is required to be done. Thirdly, what could be the likely future of Sino Indian relations?

Pre -2014:

Annexation of Tibet- 1951

On 01 October 1949 when the People Republic of China (PRC) was born Mao Ze Dong announced at the Tiananmen Square that China will annex Tibet at the earliest[2]. This was loud and clear signal for what to expect from Mao’s China in times to come. Annexation of Tibet by China was complete in 1951. India’s association with Tibet dated back to the British era first for through trade marts in 1890-93, later Younghusband’s conquest of Tibet in 1904, British Agreement with Russia in 1907, Shimla convention of 1914, and India’s military detachment in Tibet as also route reconnaissance by Maj (Later Lt Gen Z C Bakshi) in summer of 1949. While Indian political and military leadership was debating and differing the Chinese acted firmly and with speed to operationalise their plans [3] Though China had assured India that she will not use force in Tibet but the assurance was belied. In the shadows of Korean War China did use force in Tibet. Got a treaty signed with the Tibetans where the unique culture and religious faith of Tibetans were to be protected under the Chinese regime. Needless to say that China did not adhere to any of the agreements in actual practice[4].

Dispute over the Bara Hoti Grazing Grounds (Uttarakhand)-1954

Chinese troops first appeared in the Barahoti bowl in 1954. Since this was the grazing ground used by the local Indian shepherds, their presence was challenged. The Chinese left the bowl but continued to visit this area till as late as 2020, with armed soldiers on horse backs for short visits since then. The area remains a prospective conflict/flash point[5].

Bandung Conference-1955 India was one of the co sponsors of Bandung conference organised in Indonesia for 29 Asian and African nations5. Some important aspects of Bandung agreement were based on the India China agreement of Panchsheel[6].India’s commitment towards Panchsheel and acceptance of Chinese sovereignty were based on reciprocity by China in keeping Tibet as an autonomous region. China has already reneged on her commitments while India generally continued to be guided by the agreements that were signed 68 years ago[7][8].

Longju, Haji Langer and Kongka incidents- 1959

Though Barahoti came to the fore in 1954 it did not impact extremely friendly relations between India and China. The Indian Prime Minister visited China in 1954 and was all praise for Chinese development. The Chines PM visited India the same year and was greeted by large crowds. It was in this environment of bonhomie that Indian agents reported construction of a road in the Indian territory. Two reconnaissance parties were sent by India in the summer of 1958 to ascertain the facts. One of these parties led by an engineer officer was intercepted by the Chinese at Haji Langer and imprisoned for 40 days and then released with stern warning. Later an Indian Assam Rifle post at Longju was attacked by the Chinese on 26 August 1959. On 20 October 1959 the Chinese ambushed an Indian police patrol 64 kms inside the Indian territory at Kongka killing nine policemen. The mirage of Hindi Chini bhai-bhai finally disappeared. However, the disillusionment of more than a decade had already done massive harm to India’s security[9].

War with China 1962

Post 1959 there was a reluctant realization among the top political leadership in India the PRC is not so friendly as Indian leadership had believed so far. This made the Indian leadership to start military preparation to safeguard India’s territorial integrity. This is where the ‘forward policy’ was used to deploy platoon posts at all major ingress points and dominating features along the Eastern Border (known as North East Frontier Agency – NEFA). These platoon posts had negligible logistic sustainability and were ill equipped. It was believed that presence of Indian troops will justify India’s territorial claims and China will never attack these posts. This belief was not only ludicrously unrealistic in the wake of what all had happened since 1951 but was also vehemently opposed by the Indian military brass. Nonetheless the forward policy was adopted and India suffered the most humiliating military defeat from China. Chinese later withdrew from most of the captured area except Aksai Chin (38000 square kms) [10][11].

Local war with China at Nathu La and Chola (September, November 1967)

During the 1965 Indo Pak War the Chinese supported the Pakistanis by claiming Jelep La and Nathu La – both Indian posts in East Sikkim, and threatened a military attack. India obliged by withdrawing from Jelep La which was in 27 Mountain Division Sector. Nathu La was part of 17 Mountain Division under a newly promoted Divisional Commander- Maj Gen Sagat Singh. Considering the tactical importance of Nathu La Sagat refused to withdraw. The Chinese did not like this but did nothing. In 1967 an altercation between the two sides at Nathu La escalated into a full fledged armed conflict at Nathu La (11 to 15 September 1967). India defeated the Chinese inflicting very heavy casualties. Two months later the Chinese attacked Cho La another post North of Nathu La and were defeated in that clash also. This was the last time the Chinese got involved with the Indians in an armed conflict[12].

1986-87 Sumodrong Chu Valley

The conflict in the area originated from a small village Wangdung in the Sumodrong Chu valley where India had a small listening post of the Intelligence Bureau (IB) which used to be occupied during the summer and vacated in winter. The Chinese occupied this post in 1986 before the IB could come back from the summer break. The Chinese company commander asked the IB men to get away from the place since it was Chinese territory. In response Lt Gen Narhari General Officer Commanding 4 Corps responsible for the area ordered a company of 5 Gorkha to occupy Langro La ridge dominating the Chinese position. The Chinese were upset and a senior officer from the Chinese side walked up to the Gorkha Company and asked them to vacate the position immediately. The Indian Company Commander- a young captain, refused to oblige. When the Chinese walked in too close the young captain asked one of his men to fire a few rounds of Light Machine Gun over the Chinese’s head. This was enough to scare the Chinese officer as he ran away. But the incident precipitated a huge crisis in the China study group back in Delhi. Every one from the top political leadership, Army Headquarters (Chief of Army Staff) wanted the Gorkha Company to withdraw. Even written orders were given to the then Eastern Army Commander (Lt Gen J K Puri). This was the time when Lt Gen V N Sharma who was commandant Army War College took over from Lt Gen J K Puri. The new Army commander refused to withdraw and instead got entire 5 Gorkha battalion deployed at the ridge and moved artillery guns to cover them in case Chinese ventured to attack. The Chinese realised that with an Indian battalion at the ridge their position in the Wangdung village was not defensible. They quietly withdrew from the valley. In 1988 China invited the Indian PM to Beijing.[13][14]

Depsang Plains April -May 2013

This is a strategically important area – sandwiched between Aksai chin and Siachin glaciers. It is an ideal tank terrain at almost 17000 ft height. It is in Northern Sector of the LAC. The strategic Karakorum Pass is not very far from here. On 15 May 2013 an Indian patrol found Chinese in five to six tents in Depsnag Plans 19 kms inside Indian territory. This incursion has been described by some experts. The Indian troops responded in kind and occupied some other area ‘in a non threatening posture’. Negotiations were held the tents were removed and it was decided to maintain status quo. However- as we will see later this non threatening move by the Chinese resulted in occupation of 972 sq kms of Indian territory by them in that area. [15][16]

Post 2014:

Depsang Plains- Chumar and Demchok, September 2014

Soon after the new regime took over in India (26 May 14) the PLA showed up in the area of Chumar which traditionally has been under firm Indian control. Indian forces confronted the Chinese troops. Thousand odd troops from both sides remained in eye ball to eye ball contact for ten days. Incidentally, the Chinese President was on a visit to India during this period. He was informed of the incident and requested to get the PLA back. The situation was resolved and the Chinese official media did not play up this incident. On the contrary there were some reconciliatory words by the Chinese President for PLA action[17].

Depsang Plains – Burtse- 11 September 2015

At Burtse in the Depsang Plains Indian troops (Indo Tibetan Border Police - ITBP) noticed a surveillance hut constructed by the PLA. They dismantled the huts. There was a PLA platoon (30 to 40 men) near that area. There was sharp reaction by the PLA, they called in reinforcements. The Indians did the same. However, as per media reports the dispute was resolved by the military commanders on ground. Forces from both sides withdrew and as a confidence building measure Indian troops agreed to participate in joint exercise with the PLA in China[18].

Doklam- 2017

This 100 sq kms area is located at the tri junction of India (East Sikkim), Bhutan (Ha Valley) and China (Chumbi Valley in Tibet. Indian troops noticed road construction activity by the Chinese adjoining Bhutan in an area that was perceived to be no man land. The Indians virtually stopped the Chinese from the road construction activity. The stand off between India and China continued for 73 days from 16 June to 28 August 2017. Finally the Chinese withdrew from the area.[19]

Pangong Tso- 10 May 2020

Region starts where the Karakorum Range ends; North Bank of Pangong Tso is around 134 kms. There are eight fingers along this. The Chinese laid claims to all the fingers. There were fierce hand to hand fight between the Indian and the Chinese troops in first week of May 2020. Several Indian troops were injured. The Chinese had initially surprised the Indians due to the speed with which they could get additional reinforcements in place. Soon the Indians too learnt to surprise the Chinese by occupying Kailash Range. This rattled the Chinese and the two nations came to brink of war. Intense negotiations forced the Chinese to withdraw from all the Fingers at the Pangong Tso. However, some elements of PLA remained at Finger 4. The Indians have occupied Southern Bank of Pangong Tso – Rezang La, Rechine La, and Magar Hills that dominate the Chinese positions. Indian troops too have occupied dominating heights close to Finger 4. [20][21]

Galwan- 15 June 2020

This is the place in the Shyok River valley where the road from Leh to DBO passes and is dominated from some of the nearby heights. 20 Indian soldiers were martyred in the clash. China remained tight lipped on its casualties for several months. International media reports confirmed between 80 to 100 Chinees soldiers dead in the clash. During negotiation between military commanders of two nations a buffer zone has been created; the Indian troops do not have access to PP14. Meanwhile India commenced work on an alternate route to DBO through Nubra Valley.[22][23]

Yangtse (Tawang) 9 December 2022

Yangtse was occupied by the Indian troops in 1987 in retaliation to the Chinese incursion in the Sumodrong Chu Valley. On 9 December 2022 a small contingent of Indians (around 50 personnel) were confronted by around 250 Chinese troops. The Indian held the Chinese from occupying the area for more than half an hour. Meanwhile more Indian troops arrived at the area from the second layer of deployment. This changed the equation and forced the Chinese to leave. The clashes here were somewhat similar to what had happened at Galwan more than two years back. However there were no fatal injuries. The situation for the time being is diffused[24].

Analysis and the Future

There is a remarkable continuity in China’s hostility towards India since the day PRC came into power on 01 October 1949. Three distinct traits were visible soon after. First not adhering to promises made. In that annexation of Tibet was very violent. Also the cultural and religious freedoms of Tibet were not safeguarded by the PLA and the PRC regime. Thereafter a series of promises and assurances were made to be violated later. Second, China has displayed her expansionist tendencies form the beginning. She has territorial disputes with more than a dozen odd countries that include Russia. Thirdly, on all the international platforms China has harmed Indian interests. This has been the case even during the Hindi-Chini Bhai-Bhai days. In fact China does not believe in friendly nation relationship[25]. The erstwhile USSR that helped China to set up her industrial base also suffered hostilities from China (Ussuri River Clash 1969)[26]. Thus China comes out an extremely unreliable and untrustworthy nation.

India on the other hand was enamoured by the communist philosophy of total state control even before independence. Chiang Kai Shaik had visited India before 1947 and had impressed prominent leaders of Indian National Congress (INC).[27] Besides some of the top INC leaders had visited the USSR before independence and were mesmerised by the soviet model of welfare and economic growth. Even after the Chinese Communist Party overthrew Chiang Kai Shaik’s forces and assumed power on 01 October 1949 the Indian leadership gave highest priority to keeping good relations with China.

However while China maintained cohesiveness and continuity in her approach towards India the Indian response towards China has undergone major changes in three phases. The first phase commenced from just before independence to 1962 where the Indian approach to relations with China was governed by peace at any cost. The Indian leadership- especially the PM, RM and the External Affairs Minister supported by the Indian ambassador to China( K M Panikar) believed that good relations with China are extremely important and need to be maintained whatever be the cost. They also believed very firmly that China will never take military action against India[28]. The then Home Minister and several senior military officers (Lt Gen Thakur Nathu Singh, Field Marshall Cariappa, Gen Thimayya and a few others) did not support this view. Thimayya even resigned on this issue (he was later persuaded to take back his resignation). This was the period when India’s territorial integrity and external security on the North Eastern Border was compromised to the maximum extent. The damage happened to be irreversible- sharing unsettled borders with China after annexation of Tibet, loss of 38000 square kms of territory in Aksai Chin and allowing China Pakistan nexus to get stronger and effective.[29][30]

The second phase commenced after the humiliating defeat of 1962. Hectic efforts were made to spur indigenous weapon production (new Defence Production Units), increasing budget allocation for the defence forces, raising new formations, giving due weightage to what the defence experts suggested. Thus when the 1965 war with Pakistan commenced India was going through this transformation. However, though there was a belated realization of hostile intentions of China, undercurrents of fear from the Chinese might persisted. Hence, the submissiveness reflected in 1965 episode of giving away Jelep La on mere threat. This fear persisted even after Sagat Singh demonstrated in ample measure that Chinese ‘are not nine feet tall’. They can be defeated in battle. Indian troops were much superior to their Chinese counter part both at Nathu La (Grenadiers) and later at Cho La (Gorkhas). Thus in 1987 – Sumodrong Chu incident it was the Corps Commander ( Narhari) supported later by the Army Commander (V N Sharma) that got the Chinese on the back foot. Though the Indian leadership did start improving the border infrastructure as early as 1991 its pace was too slow. Besides there was a misplaced notion- till 1991, that poor infrastructure will make the defenders’ (India) job easier[31]. It was only in 2015 when the then Raksha Mantri (Late Shri Parrikar) brought the Border Road Organization (BRO) under the Defence Ministry and increased the budget allocation that the pace of infrastructure development in these areas picked up dramatically. It is this unprecedented increase in the pace of improvement of border infrastructure that has rattled the PRC especially after 2017[32].

The third phase started soon after 2014. The regime change at the centre and in many of the Indian states was not an ordinary change of guards. For the first time in many decades a majority government was elected by the Indian voters at the centre. More importantly this new government proved to be an antithesis of status quo and possessed the will and energy to set up a new narrative. Its subsequent victory in 2019 general election placed a stamp of approval by the electorate for the new narrative. This phase too commenced with traditional hand of friendship extended by the new government to the Chinese. But the hand quickly changed into a hard fist once the Chinese commenced their old game of pushing and threatening at Chumar. Thereafter Indians have been proactive and robust in their response both militarily and in geopolitical posturing. The Ministry of External Affairs started calling spade a spade. Militarily the government shifted the defensive and offensive capabilities towards China. Besides increasing the troops deployment towards China by 50000, two strike corps were earmarked for the Eastern Border. A special brigade was raised for Sub Sector North in the sensitive DBO and Aksai Chin area. To counter the Chinese armour threat in the Depsang plains India inducted sufficient quantum of its main battle tanks (Arjun and T 90) in the sector. The ground deployment has been supported by an effective air defence, missiles (Brahmos) and offensive air support elements. The air field at DBO is fully operational and is being used. All these factors are clearly visible in the nature of conflicts that have been addressed by India after May 2014[33].

In the future for about next five to ten years India will continue to be proactive and at times aggressive in facing belligerent China. Each Chinese move in the military, economic, international and cyber domains will be actively countered without fear of repercussion and without unnecessary noise. This will be accompanied by fast pace of development in the border area adjoining China not only in terms of military logistics but with citizens’ ease of living in focus. India will increase fire power, mobility, surveillance, air defence and offensive air capabilities with indigenous defence production as was being seen during the last few incidents. Coupled with preparation in the military domain India will continue to improve her economic power by good fiscal discipline, increasing manufacturing base to replace China as the global hub of manufacturing. In specific context of China India has reduced her import from China by 168 billion INR from July to October 2022[34]. However India’s trade deficit with China is still all time high at 100 billion dollars in 2022[35]. Given India’s post COVID 19 performance and the way the Indian foreign office addressed the Russia- Ukraine war it is highly probable that India will start enacting the role of dominant player in the game China has been playing with India for the last seven decades.

There can be three probable outcomes of this posturing. First with India’s growing global footprints and clout coupled with increasing military preparedness China may see reason and opt for real long time settlement of borders. However for this to become reality China may have to give up her claim on the Aksai Chin which forms part of Jammu and Kashmir. Indian parliament has passed a bill (22 Feb 1994) claiming entire Jammu and Kashmir as part of Indian territory[36]. Also China will have to grant autonomous status to Tibet as this was an essential clause in India’s acceptance of one China policy and Chinese sovereignty over Tibet. Second there can be a local conflict the way it happened in Nathu La and Chola in 1967. India has a good chance of capturing some strategically important ground especially in Aksai Chin. Thirdly, conflict situation may remain unchanged. Given the current situation the last option appears to be most likely. Unfortunately this will be detrimental to both India and China.

References

[1]https://theprint.in/defence/5-maps-that-tell-you-all-you-want-to-know-about-india-vs-china-in-ladakh/507289/

[2]PJS Vinay Shankar, G G Dwivedi, Bharat Kumar, Ranjit Singh Kalha, Bhavna Tripathy (eds.) (2015), 1962: A View from the Other Side of the Hill, New Delhi: Vij Books India Private Limited

[3]Claude Arpi , Tibet: The Last Months of a Free Nation India Tibet Relations 1947-62 Vij Books India Private Limited ( United Services Institutions of India – New Delhi) 2017, ISBN 9789386457219

[4]http://www.indiandefencereview.com/news/is-india-paying-the-price-for-abandoning-tibet/

[5]https://history.state.gov/milestones/1953-1960/bandung-conf#:~:text=In%20April%2C%201955%2C%20representatives%20from,%2C%20economic%20development%2C%20and%20decolonization.

[6]https://www.mea.gov.in/Uploads/PublicationDocs/191_panchsheel.pdf

[7]https://www.claws.in/static/IB-305_Boundary-Dispute-of-Barahoti-Bowl-in-Central-Sector-An-Assessment.pdf

[8]https://www.orfonline.org/research/we-had-a-one-china-policy-for-long-its-time-for-a-relook/

[9]http://www.indiandefencereview.com/spotlights/chinese-shadow-darkens/

[10]Ibid 2, also refer to Henderson Brook Report ( https://www.google.com/search?q=henderson+brooks+report+pdf&rlz=1C5CHFA_enIN1014IN1014&oq=Henderson+Brook+&aqs=chrome.2.69i57j0i10i512l7j0i10i22i30l2.9430j0j15&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8

[11]V K Singh Maj Gen , Leadership in the Indian Army Biographies of Twelve Soldiers , Sage Publications 2005, ISBN 9780761933229

[12]https://www.claws.in/static/IB-252_Nathu-La-September-1967-and-Galwan-Valley-June-2020-Lessons-and-Future-Strategies-for-

[13]Probal Das Gupta (2020), Watershed 1967: India’s Forgotten Victory Over China, New Delhi: Juggernaut

[14]https://caravanmagazine.in/interview/general-v-n-sharma-indian-china-conflict-wangdung-tawang-1987-mcmahon-line

[15]http://www.indiandefencereview.com/the-sumdorong-chu-incident-a-strong-indian-stand/

[16]https://www.orfonline.org/research/depsang-incursion-decoding-the-chinese-signal/

[17]https://idsa.in/idsacomments/CurrentChineseincursionLessonsfromSomdurongChuIncident_msingh_260413

[18]https://idsa.in/idsacomments/BorerStandoff_rdahiya_290914

[19]https://theprint.in/defence/how-india-and-china-resolved-three-major-stand-offs-in-the-modi-era/430594/

[20]Ibid 18

[21]https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-56147309

[22]https://theprint.in/opinion/if-india-loses-grip-on-kailash-range-pla-will-make-sure-we-never-get-it-back/542327/

[23]India.pdfhttps://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/india-china-ladakh-bro-nubra-valley-dbo-pangong-tso-lake-1952640-2022-05-22

[24]Ibid 12

[25]https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/india-china-ladakh-bro-nubra-valley-dbo-pangong-tso-lake-1952640-2022-05-22

[26]Henry Kissinger, ‘ World Order’ Penguin Books 2015 ISBN 9781594206146

[27]Origins and Consequences of Soviet Chinese Border Conflict 1969 https://src-h.slav.hokudai.ac.jp/coe21/publish/no16_2_ses/03_ryabushkin.pdf

[28]Durga Das, ‘India From Curzon to Nehru & After’ Collins St James Palace London 1969

[29]Ibid 28

[30]Ibid 28

[31]Ibid 9

[32]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eP8dTver09w ABP News Clip

[33]https://www.orfonline.org/research/urgent-need-to-improve-indias-border-infrastructure/

[34]https://news.abplive.com/news/india/india-china-border-dispute-from-ladakh-to-northeast-6-indian-army-divisions-shifted-to-counter-pla-s-threat-1531709

[35]India imports from China https://tradingeconomics.com/india/imports-from-chinaTimes of India 14 January 2023

[36]https://newsonair.gov.in/News?title=Centre-aims-to-implement-Parliament%26%2339%3Bs-resolution-to-reclaim-remaining-parts-of-PoK%2C-says-Defence-Minister-Rajnath-Singh&id=449945

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://www.iasparliament.com/uploads/files/india-china-border-dispute.png

Thank you for this wonderful piece of information

Post new comment