If someone has to physically locate the Silk Road, then they would usually find a region from the main landmass of China to the ancient Roman Empire. The route in between, also touches the northern region of the Indian subcontinent as well as the Central Asian countries.[1] When the Silk Road is demarcated as a location between the East and West, the endpoints of the Silk Road often are emphasised, i.e., China and the Roman Empire. The points ‘in-between’, which are often overlooked, sometimes might be thought of as less significant. But if we thematically study the Silk Road, one would find that different parts of the Silk Road would come into prominence depending on the subject we are examining. For instance, when we take the theme of silk trade, the significance of China would perhaps be higher than any other location within the Silk Road, say for instance, India’s. But when it comes to themes like tradition or culture, regions like India might gain more significance. India’s interaction with the Silk Road gained momentum with the arrival of Buddhism. In other words, the attention for Indians among the various regions covered by the Silk Road increased due to the impact of Buddhism.[2] The period of Asoka Maurya is often credited for the spread of Buddhism from India to various other locations towards the West, which gradually resulted in merging with a lot of Hellenistic traditions.[3]

Under the rule of the Kushana king, Kanishka (144-172 AD), Buddhism did thrive further and spread to many regions, including Gandhara and in the next few centuries, Buddhism within the scope of the Silk Road spread to places. For instance Bamian was one of the significant Buddhist centers that existed from around 5th century AD. One of the reasons for its importance lies in the fact that it was located at a strategic point on the map – at an intersection of roads that lead to prominent destinations, such as Persia, India, Tarim Basin and China.[4]

It is said that Buddhism travelled to China at least half a century before the beginning of the Common Era.[5] Since then, many travellers and pilgrims travelled from China to India for visiting holy sites and in search of the scriptures and other information, which were relevant for establishing monasteries. It cannot be suggested that the spread of Buddhism, whether to the West or to China was a single one-directional event. Rather, it was spread through a complex process with the participation of different groups of people, which includes merchants, kingdoms, monks, pilgrims, medicinal traditions, artists, and so on.[6] In the midst of cultural encounters on the Silk Road, there are many Buddhist travellers or pilgrims from China who visit India through the Silk Road. Their travel records suggest not only the things that they saw but also suggest about the developments in the region they were coming from. Each of these pilgrims is travelling in different time periods. This article looks at some of the changes over time in the regions, the nature of interactions through their travel record.

Though Buddhism was spreading across different regions, India remained a land that was getting conceptualised as a ‘Holy Land’ among the new scattered Buddhist world. This was mainly because India, being the land of Buddha and with the already existing monasteries, scriptures and practices of India became a reference point for various other regional Buddhism. This does not mean that Buddhism was exactly replicated in those regions, but rather the tradition was organically localised. Throughout this process, India played the unique role of a pilgrimage spot. The term for pilgrimage in Chinese, ‘quijing’ literally means ‘fetching scriptures’.[7] In that case, India being a major site from where Buddhist scriptures were taken and a prominent site frequently visited by pilgrims, it is highly possible that this Chinese term developed in the cultural context of Buddhism and its relationship with India. We know that there were many travellers or pilgrims from China who had visited India during various periods. The accounts that they have left are considered significant for Indian history. Generally, there is an assumption that their visit to India was ‘only’ for a specific purpose. From such a perspective, all the other records that they were making from regions like Central Asia could be seen as their observations that they had made casually on the way. Often, the Central Asian accounts that they have left are considered less significant because of the presumption that their focus was only on India. In other words, the assumption could be that exploring the Central Asian Buddhist world was a secondary concern for these pilgrims.

While understanding the unique significance and concern these pilgrims had for India, it is equally important to look at some of the instances, which would suggest that exploring the Central Asian Buddhist world was also important for them. Such a way of looking at India in relation with the silk route would make us understand it as a larger, highly mobilised network, where pilgrimage, especially to India was an important cultural practice. In other words, such a reading of their accounts without separating India with other regions of Silk Road would tell us about the network as a whole, where the Indian subcontinent did have a unique importance especially when it comes to subjects like tradition and culture. In this article, the references are restricted to a few Buddhist pilgrims who have left us with a good number of details, in the form of travelogues.

Silk Road as Pilgrimage Road in the Accounts of

(i) Faxian (337-422 C.E) is known to have travelled India, Central Asia and South-East Asia by foot from China. His journey is recorded in his travelogue, ‘A record of Buddhist Kingdoms’.[8] Though majority of the kingdoms that gave patronage to Buddhism might be in India at that time, his title never emphasised a particular geographical boundary. The motive for his collection of scriptures from India could be understood within the context of increasing popularity of Buddhist tradition back in China. Each space would have a unique living culture, and to live in that culture someone from outside might have two options, either to re-locate themselves, or to take instances and practices from that culture and it take back to his or her homeland. Faxian himself might belong to the second category, he visits India with utmost love and respect, which he had for this Buddhist homeland, but he eventually wants to go back and establish the observations like Vinaya rules back in emerging monasteries of China.[9] This ‘take away’ by default is also a case of localisation.

Some of the important sites in Central Asia, which he had visited are as follows: Lanzhou, Dunhuang, Loulan, Karashahr, Khotan, Tashkurghan, Darel, and so on.[10]

Throughout his journey, he has encountered people from various ethnicities. Faxian notes about the local monasteries in Central Asia that provided shelter and temporary arrangements to wandering monks.[11] This suggests that the Central Asian region was frequently visited by traveller monks, perhaps, those that came mostly to India from China. These Central Asian monasteries would have played their role as stations, in making their journey of the monks simpler. Since these monasteries possibly would often accommodate different travellers from various regions, they would have played an important role in maintaining the network.

These monasteries also received a good amount of income through the merchants and traders who had used their services. When we understand this as a network, we would find that there is hardly any ‘isolated’ Buddhist holy land anywhere along the Silk Road; this applies to India as well. Even the pilgrimage sites or monasteries with prominence were sustaining at that period because of a wider ecosystem. Faxian himself suggests this ecosystem or network spanning across boundaries. He finds that in a place called Loulan, he encountered people in appearance and dressing as Chinese but followed many cultural practices of India.[12] This is an example of how cultures do travel without rigid boundaries. Therefore, a mosaic separation between the Buddhist homeland India and Central Asian parts would seem minimal, if not disqualified when we see from this particular context.

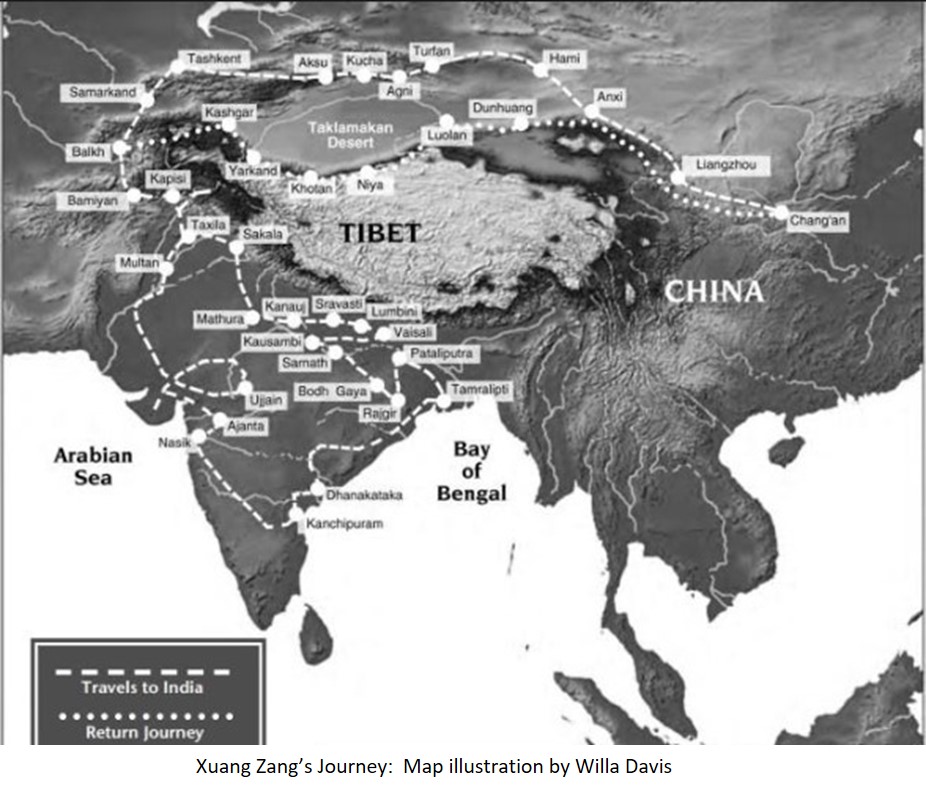

(ii) Xuang Zang (600-64) who visited the Indian subcontinent during the reign of Harsha in the 7th century also identifies the cultural impact of India on Central Asia. He identifies the use of Indian scripts in the Central Asian regions of Yanqi (Agni), Kuchi and Khotan.[13]

From the work of Xuanzang, it appears that his visit to the Indian subcontinent is both as a devoted pilgrim and as an unofficial diplomat for Tang China to Harsha’s court.[14] Hence he is mostly known as someone credited for strengthening the future relationship between Kannauj and Tang court.[15] But his visits to other sites in the silk road that are outside Harsha’s kingdom are also remarkable. As an insight from this, Prof. Tansen Sen says, “Xuanzang set out on his pilgrimage to India without formal authorization from the Tang court. His illegal departure from China may have been one of the reasons why Xuanzang deliberately sought an audience with important foreign rulers in Central and South Asia”.[16]

Xuang Zang is known to have visited more sites than Faxian and could procure more scriptures and visit different monasteries located in the homeland of Buddha. But along with the Indian sites, the Central Asian sites of Xuang Zang also find a more or less equal number of increases from that of Faxian. Interestingly, what makes Xuang Zang unique is that both his arrival to India and return from India was through land route.[17] This perhaps would have enabled him to travel to more in-land Buddhist sites in India and Central Asia than many other travellers.

This is in contrast to,

(iii) Yijing (653-713), who completely missed out on the Central Asian journey because he took a maritime silk route on his way to India. Yijing’s Memoirs of Eminent Monks tells us that some monks took a land route to India via Tibet and Central Asia, and another set had a sea journey via South East Asia.[18]

For Yijing, taking the maritime silk route enabled him to take account of Buddhist scholarship in Srivijaya. In Yijing’s description, the city of Srivijaya was home to “more than a thousand Buddhist priests whose minds are bent on study and good works.”[19]

By his time, both Central Asia and South-East Asia were an extension of the wider Buddhist world. The choice of these monks, whether to travel via land or sea (Silk Route or Maritime Silk Route) might have been dependent on the pilgrimage sites they wanted to visit. This must also be a choice taken by the monks based on their monastery networks and orders. This also suggests that the pilgrimage site for them would not have been just the destination, but the journey itself, the stations they stayed at, people they met, holy sites they visited, and monasteries they stopped during their journeys.

What we have seen above was about Buddhist pilgrims, who were fascinated to visit various pilgrimage sites with a special interest to explore the diverse Buddhist traditions spanning across. The argument here is, though, in their pilgrimage, India might have been a unique place, but their references to Central Asia cannot be reduced merely as a traveller’s reference. For them, the ‘pilgrimage’ was inclusive of all of these stations, where the destination is connected to the larger network of the Silk Road (both inland and maritime).

The word for pilgrimage in Chinese is ‘quijing’, which translates to ‘fetching scriptures’ stands true as India had significance as a source for these scriptures. But even to ‘fetch scriptures’ or to reach India, they had to make use of the wider Buddhist network, and the Silk Road played an important role in fostering this network. To extend this argument, let’s take one more instance from a pilgrim who is unique from his above-mentioned counterparts.

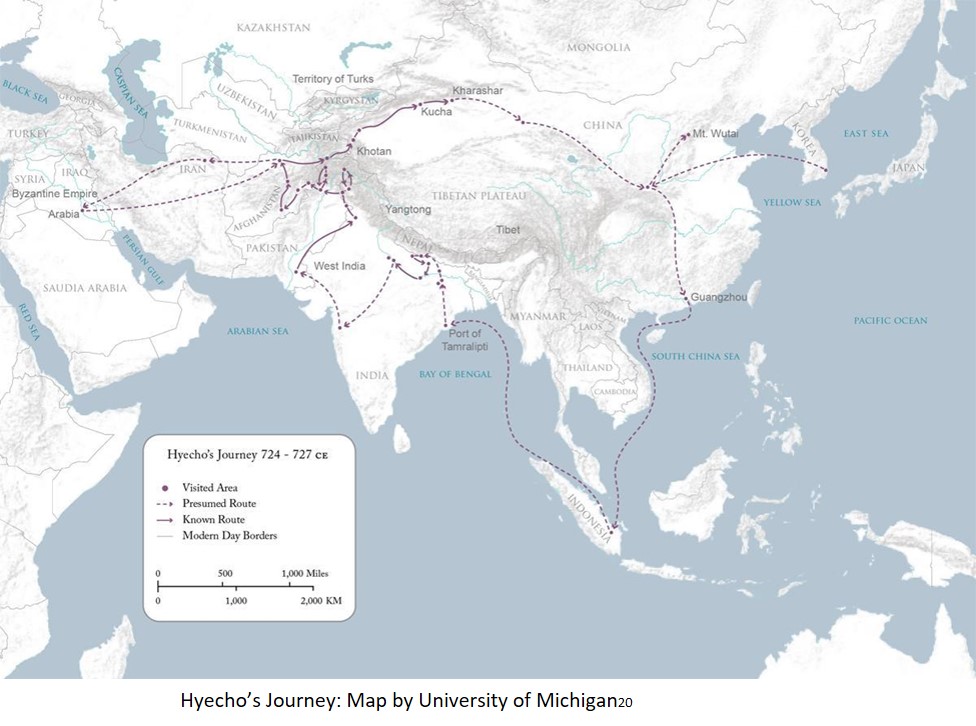

(iv) Hyecho (704-787), a monk originally from Korea, sets his journey to visit India from China. His travelogue, ‘An Account of Travel to the Five Indian Kingdoms’ is unique for various reasons.

It is considered the first known overseas travelogue penned in Chinese by a Korean traveller. It contains details on the cultural and political situation of India and central Asia that existed at that time. The names of the five Indian kingdoms that are mentioned in the title of the work stand for West, East, North, South and Central India. The work also has information on the Byzantine Empire, along with many other Central Asian states.[20] Geographically, it covers a large part of the Silk Road.

His travelogue was written at a time when the rise of Buddhism was at its peak in India, especially Mahayana Buddhism.[21] Unlike other famous travellers, his travel account also captures the beginning of Tibetan Buddhism. He is also famous for his extensive travel upto Iran along the Silk Road.[22] But unlike other pilgrims mentioned above, his interest was not only to explore Buddhist traditions alone; rather, he was interested in the other local practices and customs of the regions he visited.[23]

There is another striking contradiction between Hyecho and his predecessors. Unlike other famous pilgrims, Hyecho did not travel back to his land with any translated scriptures.[24] Would this make him any ‘less pilgrim’ if we go by the literal translation of the ‘quijing’ as fetching scriptures? It is in this circumstance that the context in which Hyecho made his travel becomes interesting. To the other early travellers from China, ‘fetching scriptures’ from India was of major importance, as the Buddhist world and monasteries were under formation in various regions. By the time Hyecho made his travels, the Buddhist tradition had become more independent and popular, and monasteries had become more mature in regions like China, Korea, Tibet, and even India. Thus for Hyecho, the concern of pilgrimage became more about capturing the diversities of Buddhism, which spanned across the regions than about fetching scriptures from India. This ‘out of the scripture’ interest might have led him to think about traditions even outside Buddhism, which makes his pilgrimage account unique.

Conclusion

In the popular discourse of the Silk Road, China and the Roman Empire often get more attention due to various reasons. The other regions are often sidelined or considered relatively less significant. Such an approach might have led to several consequences, in terms of our understanding of the Silk Road as a whole. However, if we attempt to alter this approach by studying the Silk Road thematically, we might find different regions coming to prominence based on the subject we take up to examine.

This article argues that, when it comes to themes like culture and tradition regions like India get more prominence. For example, we could perceive the Silk Road as a pilgrimage road to India based on some of the travel references used by pilgrims, who were coming to ancient India. A pilgrimage is often conceptualised as a journey between a particular starting point and a destination, which is usually a holy place. The points or stations in between are often seen only as a ‘medium’, which may connect the pilgrim to the pilgrimage spot. However, it could be said that while India may have been a special location for them during their journey, their references to Central Asia cannot be reduced to the conventional remarks of travellers. They considered all of these stops to be part of their ‘pilgrimage,’ which included India as a connection to the Silk Road's wider network (both inland and maritime).

Bibliography

- A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fa-hsien of Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline. Translated by James Legge. Czechia: Good Press, 2019.

- Behera, Subhakanta, “India's Encounter with the Silk Road.” Economic and Political WeeklyVol. 37, No. 51 (December, 2002): 5077-5080.

- Basham, A.L. The Wonder That Was India. New Delhi: Picador India, 2019. Haicheng, Ling. Buddhism in China. Translated by Jin Shaoqing. China Intercontinental Press: 2004.

- Koreatimes. “Silla travel journal returns to Korea. ” Accessed 28 May, 2021. https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/art/2010/06/135_68456.html.

- Millward, James A. The Silk Road: A Very Short Introduction. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

- Sen, Tansen. Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, 600–1400. Honolulu: Association for Asian Studies and University of Hawai'i Press, 2003.

- Sen, Tansen. “The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing.” Teaching About Asia through Traveler’s Tales Volume 11:3 (Winter: 2016): 24-33 http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/travel_records.pdf.

- Wriggins, Sally. The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang. Washington DC: Westview Press, 2003.

- Yokota, Keiko., Jun, Ha Nul., Sinopoli, Carla M.., Bloom, Rebecca., Lopez Jr., Donald S.., Carr,

- Kevin Gray., Chan, Chun Wa. Hyecho's Journey: The World of Buddhism. United Kingdom: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Endnotes :

[1]James A. Millward, The Silk Road: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013), 20.

[2] Subhakanta Behera, “India's Encounter with the Silk Road,” Economic and Political Weekly Vol. 37, No. 51 (December 2002): 5078.

[3]A. L Basham, The Wonder that was India (New Delhi: Picador India, 2019) 263-268.

[4]Behera, “India's Encounter with the Silk Road,” 5078.

[5]Ling Haicheng, Buddhism in China, trans. Jin Shaoqing (China Intercontinental Press: 2004), 1.

[6]Tansen Sen, Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade: The Realignment of Sino-Indian Relations, 600–1400 (Honolulu: Association for Asian Studies and University of Hawai'i Press, 2003).

[7]Donald S. Lopez Jr, Rebecca Bloom, Kevin Grey Carr, Chun Wa Chan, Ha Nul Jun, Hyecho’s Journey: The World of Buddhism (Chicago. London: The University of Chicago Press: 2017

[8]A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms: Being an Account by the Chinese Monk Fa-hsien of Travels in India and Ceylon (A.D. 399-414) in Search of the Buddhist Books of Discipline, trans. James Legge (Czechia: Good Press, 2019).

[9]As an example for the first category, Faxian himself talks about Daozheng, one of the monks who came along with him and refused to travel back to China. See . Legge, A Record of Buddhistic Kingdoms, 16–17.

[10]Tansen Sen, “The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing,” Teaching About Asia through Traveler’s Tales Volume 11:3 (Winter: 2016): 25

http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/special/travel_records.pdf.

[11]Tansen Sen, “The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing,” 26.

[12]Ibid 26.

[13]Sally Wriggins, The Silk Road Journey with Xuanzang (Washington DC: Westview Press, 2003).

[14]Tansen Sen, “The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing,” 28.

[15]Sen, Buddhism, Diplomacy, and Trade, Chapter 1

[16]Tansen Sen, “The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing,” 29.

[17]Tansen Sen, “The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing,” 29.

[18]Tansen Sen, “The Travel Records of Chinese Pilgrims Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing,” 28.

[19] http://hyecho-buddhist-pilgrim.asian.lsa.umich.edu/se_asia.php

https://hyecho-buddhist-pilgrim.asian.lsa.umich.edu/

[21]Chung Ah-young, “Silla travel journal returns to Korea,” Koreatimes. Accessed (28.05.2021), https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/art/2010/06/135_68456.html.

[22]Donald S. Lopez Jr, Rebecca Bloom, Kevin Grey Carr, Chun Wa Chan, Ha Nul Jun, Hyecho’s Journey: The World of Buddhism, 6.

[23]It is to be noted that his visit was prior to the rise of Islam in Central Asia. Donald S. Lopez Jr, Rebecca Bloom, Kevin Grey Carr, Chun Wa Chan, Ha Nul Jun, Hyecho’s Journey: The World of Buddhism, 6.

[24]Donald S. Lopez Jr, Rebecca Bloom, Kevin Grey Carr, Chun Wa Chan, Ha Nul Jun, Hyecho’s Journey: The World of Buddhism, 8.

[25]Donald S. Lopez Jr, Rebecca Bloom, Kevin Grey Carr, Chun Wa Chan, Ha Nul Jun, Hyecho’s Journey: The World of Buddhism, 5.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Post new comment