Reverence to others comes out as what one has inherited and learned from their elders or ancestors. As Martin Heidegger puts it, “In giving thanks, the heart gives thought to what it has and what it is.”1 The praxis of revering would vary based on the learned ethos and values that they have inherited from their ancestors. This article tries to narrate two civilisational gestures of reverence through figures of thought from the traditions of West and India.2 Arguably, these gestures differ based on the kind of knowledge the respective traditions have received from their ancestors. Reflecting on them also would help us to understand how these two traditions are cultured to perceive their past, present and future or approach subjects like progress, change and continuity.3

A gesture is a way of articulating meaning through bodily actions. It could also exist verbally in the form of metaphors. Perhaps, the most famous usage of the metaphor ‘Standing on the shoulders of giants’ is by Sir Isaac Newton in a letter to his friend, where he writes, “If I have seen further, it is only because I have stood on the shoulders of giants.”4 Though he wrote it in the 17th century, from where he wrote such a thing would lead us back to the European Middle Ages. The earliest known expression of this metaphor is attributed to Bernard of Chartres5 about whom theologian and Bishop of Chartres John of Salisbury (12th c) spoke about in the following way.

“Bernard of Chartres used to say that we [the Moderns] are like dwarfs perched on the shoulders of giants [the Ancients], and thus we are able to see more and farther than the latter. And this is not at all because of the acuteness of our sight or the stature of our body, but because we are carried aloft and elevated by the magnitude of the giants.”6

In short, the metaphor tries to convey that we see more not because we are great but because our ancestors were giants. However, the idea remains that the vision of the dwarfs is far stretched than the people of the past who were giants. Despite their physical disadvantages, dwarfs receive an added chronological support from the past to see more from the present.

A casual attempt to define ‘modernity’ usually contains words related to temporality on a positive note. Words such as ‘change’, ‘movement’, ‘progress’ are all indicative of an addition for betterment with the course of the linear movement of time. According to Hans Gumbrecht, being ‘modern’ is not only a standpoint of the present against a perceived past, but also it is about the creating and qualifying of a ‘new’ by which the ‘old’ gets automatically created and disqualified along.7 This way, we tend to experience time as an extent that flows steadily without turning back or in short, time as a mechanism that is in control of itself.8 This metaphor reveals to us how a 12th-century expression of gesture has consistently influenced the notion of progress, change or the understanding of temporal registers constructed in the Western world.9

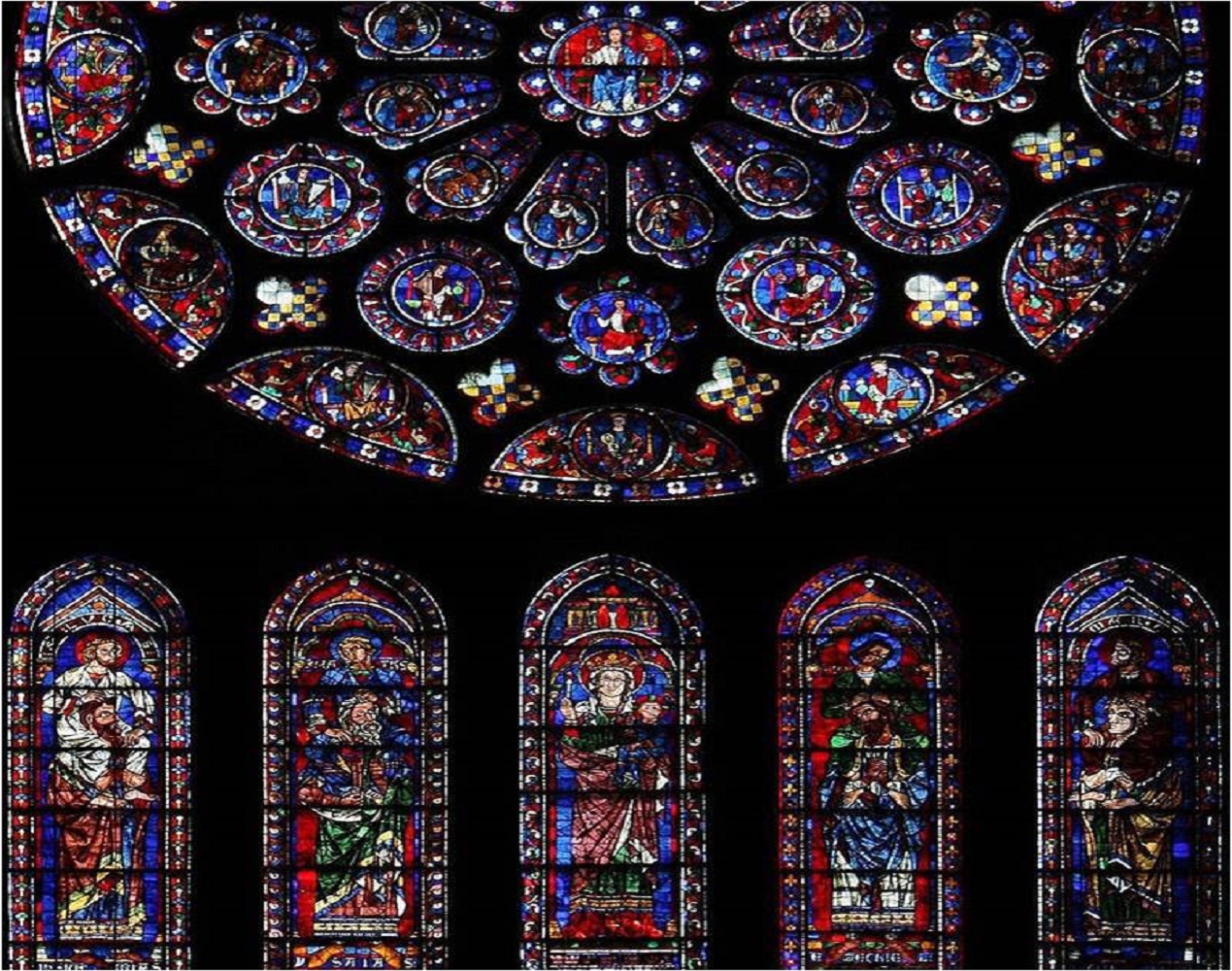

The famous depiction of this metaphor appears to be at Chartres Cathedral, which displays the expression of an ‘addition’, where the four apostles of the New Testament are standing on the shoulders of four prophets of the Old Testament looking up at the messiah.10 It tries to convey here that while the ‘Old’ remains as a foundation for the ‘New’ Testament to emerge, the New Testament exceeds the Old Testament to ‘progress’. Here the Old Testament is not discarded; rather it is treated with reverence as the significant preliminary step taken so that the ‘new’ could succeed. In other words, the category of ‘Old’ is created and preserved so that the ‘New’ could compare itself with, for its own self-understanding; on how far it has seen beyond the old one.11 It is when the notion of time is generalized and an unrealistic future is envisioned ahead that the individual actions are directed towards a collective destiny. A cultural need then emerges to ‘progress’ and constantly create and recreate ‘Old’ and ‘New’.

One could reflect this formulation on how the image and definition of ‘traditional’ is used to compare, understand and legitimize what is ‘modern’ and in deciding progress, a scenario which perhaps is relatable to the postcolonial world. In historiography, this phenomenon is best reflected through temporal boundaries constructed as ancient, medieval and modern.

Leaving this aside, let us now try to explore what an Indian alternative for this metaphor of reverence could be. This will have a lot to reflect on how Indian culture tends to look at subjects like ‘progress’, ‘change’ and ‘continuity’ or about past, present and future. Here, the article would attempt to illustrate this with examples from two modern Hindu thinkers namely, - Mahatma Gandhi and Swami Vivekananda, who have attempted to place Hinduism along with socio-political complexities of the 18th and 19th centuries.

Gandhi’s Expansion of Vyāsa

Mahatma Gandhi who is known for being critical about several aspects of modern civilisation and industrial progress,12 calls for an ‘expanded’ understanding of the cultural term Yajña in the socio-political context that he was in, which itself is a matter of paying reverence to the fathers, according to him,

“There is no harm in enlarging the meaning of the word yajña, even if the new meaning we attach to the term was never in Vyāsa’s mind. We shall do no injustice to Vyāsa’s words by expanding their meaning. Sons should enlarge the legacy of their fathers”13 (emphasis added).

Now the question appears whether this is a statement that is comparable with the metaphor that we used earlier - standing on the shoulders of giants; if so, how could it be from Gandhi, a figure who is known to have resisted the ideas of teleological progress of modernity? To put it in other words, does Gandhi mean in the name of ‘expanding the meaning’ or ‘enlarging the legacy of fathers’ to manipulate the ‘old’ by being in a self-assumed position of progress? Prof. Vishwa Adluri and Joydeep Bagchee in The Nay Science look at this question in a different context by comparing Gandhi’s interpretation of the Gītā against the German Indological framework.14 Here, they have shown what essentially Gandhi meant by ascribing a ‘new’ (expanded) meaning of Yajña, which is unintended by Vyāsa.15

In Gandhi’s understanding of the word, Yajña is not an other-worldly act, which is divorced from the socio-political context of India’s freedom struggle.16 From expanding the meaning of Yajña ascribed by Vyāsa and other commentaries, Gandhi is trying to move it from a cognitive/evaluative frame to an actional frame of his contemporary times, for a direct experience of the Gītā.17 Because the Gītā itself provides room for such an ‘expansion’ or contextualization for people to relate, experiment and respond. Similarly, the Hebrew Bible of the Jews also provides room for an ‘addition’, since it takes its bearing from the future, awaiting the arrival of the Messiah, which opens the way for the ‘New’ to emerge from the foundation of an ‘Old’ in a linear structure. But in the case of Gandhi and his forefathers (Vyāsa), a semantic linear shift from ‘old’ to ‘new’ is not required. Gandhi was present in such a situation where he could make use of the wisdom in a different way, which Vyāsa would have used pertaining to the scope of the circumstances of his living period.

This is to say, even in the case of such an expansion of the term; Gandhi never identifies himself to see more than his ancestor (Vyāsa). When Gandhi talks about the new meaning of Yajña that Vyāsa would not have thought is not to be taken as Gandhi limiting the unlimited contextualization of the term Yajña. Rather, he seems to be talking about a colonial context in which Yajña is used, which Vyāsa would not have imagined. The traditional Gītā anchored in the past for Gandhi still stands valid as a normative reference point. What Gandhi does here is to learn it again in his present, instead of ‘adding’ to result in a fulfillment of progress. Thus Gandhi’s ‘expansion’ of the term comes out as a continuum from Vyāsa, if not as a distinction between ‘Old’ and ‘New’ and to stand on the shoulders of the ‘old’.

Sri Ramakrishna’s Infinite Breadth

Swami Vivekananda’s contribution to make Hinduism in its contemporary form as a world religion is prodigious. This happened not only out of his efforts to collectivize an identity within, but rather it was also because of his constant engagement with the Western world. Hence, the name of Swami Vivekananda often comes along with adjectives like ‘modern monk’ and is sometimes categorised as a ‘neo-Hindu’ (though this usage is often used in a polemical sense). According to Prof. Makarand Paranjape “...Vivekananda saw himself as the equivalent of a modern rishi. That gave him the moral courage to assert his adhikara or authority to change the parampara. As he thundered in one of his Chennai addresses, ‘Sankara did not say so, I Vivekananda, say so.’ He was an agent and author, not merely transmitter or carrier of tradition. This marks his difference from a guardian or champion of ancient revelation; he was, instead, a participant and shaper of a Sanatana dharma, adding his experience to the pool of sruti.”18

Yogananda who was a disciple of Sri Rama Krishna Paramahamsa asks Swami Vivekananda whether he is contradicting with their ‘traditional’ Guru. His worry was, “You are doing these things with Western methods. Should you say Sri Ramakrishna left us any such instructions?”19

The question here is whether Vivekananda is bringing something ‘new’ (non-traditional), which would potentially make his Guru(s) ‘Old’. In other words, if one has to rephrase this question, if Yogananda permits, it could be like “..are you standing on the shoulders of Paramahamsa ?”

Vivekananda responds, “Well, how do you know that all this is not on Sri Ramakrishna’s lines? He had an infinite breadth of feeling, and dare you shut him up within your own limited views of life.”

One could argue from the generic history criticism perspective that it could have been Vivekananda’s intention to legitimize his intention to ‘modernize’ Hinduism for which he took bearing from the name of a ‘traditional’ master Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa. But emphasis here is to analyse this dialogue from his mode of reverence. When Vivekananda says Ramakrishna had infinite breadth, what he wants to experience is continuity from his guru, not a progress, nor a decline. This is to say both rupture and continuity rely only at the experiential level. For Vivekananda, adopting the contemporary systems, re-appropriating themselves in the present does not appear as a confrontation with his past. Rather, the inherited knowledge is appropriated to the modern systems, to protect the knowledge itself, and which would in turn transform the modern system to which the inherited knowledge is adopted into.

Conclusion

After looking at both these instances from Gandhi and Vivekananda, one could ask where do they metaphorically find themselves as inheritors of a parampara, standing on the shoulders or sitting at the feet? While the former suggests the meaning of discovering the truth by building or adding on previous discoveries (like how the New Testament developed out of the Old one), the latter suggests constant reflection of an existing knowledge over ‘addition’. Also, as far as the latter is concerned, each time, it is a new learning and a new application of knowledge to the changes around. A perception from the standpoint of the former metaphor (western) might appear as, in Indian knowledge traditions, the ancestors do not welcome questioning and criticisms or any ‘additions’ as their disciples are at their feet and not on their shoulder. It should not sound impossible to think about questioning the ancestors and yet revering them. In fact, it is through constant questioning and argumentation that the Indian Knowledge Traditions have expanded themselves.20 It was not morally dilemmatic for Gandhi to say, “Even if Vyāsa had defined the words which he used, we would ask why we should accept the meanings given by him.21 He suggests from this statement that there is no compulsion to either accept or reject the meanings given by Vyāsa, rather it is to be experienced by individuals through questioning and learning it a new post inheritance. Similarly, Vivekananda’s self-assertiveness and confidence to shape Sanātana Dharma for modern times share the same level of spirit, which Gandhi also seems to have, though their field of actions or contexts slightly vary from each other, but the larger template of Dharma remains constant.

In such a scenario, progress does not appear as a march towards a proposed utopian future; rather progress seems to be about duties and responsibilities for the contemporary times, which an individual and society accepts by reflecting, contextualizing or expanding on what has been inherited. This thought in Indian culture could be reflected in one of the most famous verses on Karma Yoga from the Bhagavad Gītā as well, which tells, “Thy right is to work only [in the ‘present’], but never to its fruits [results in ‘future’]; let not the fruit of action be thy motive, nor let thy attachment be to inaction.”22 In contrast, if we look at the modern notion of ‘progress’, it conditions people to work for a desired destiny (individual and collective) in the future, even as it appears eventually non-viable. According to Aleida Assman, “This is how time becomes generalized and takes on the form of an overarching process that frames individual actions and gives them direction.”23 Here, the implication is not to understand and classify the Western notion of progress as ‘optimistic’ and the Indian cultural notion as ‘pessimistic’, which does not plan for the future at all. Even for one to act responsibly in the present, an objective assessment about the possible implications of the future caused by the current actions is required to be known. Thus, the notion of Karma Yog a from the Bhagavad Gītā seems to convey that the fulfillment of action does not rely on the result (future event); rather its fulfillment is in performing the action itself as Yajña. Therefore, the future comes as a consequence, which cannot be totally determined before performing the action. Hence, instead of taking bearing from the future (results), emphasis is given to performing the action itself. This is quite different from the future perceived as an unchecked promise with ‘utopian ends’ (results) in early modernity, which tends to see the future as eschatological in nature or in other words, to expect the future as a completely different world, which is ideal.24

In brief, the mode of reverence is also a way of looking at one’s past, which is also determined by how a culture anticipates the future.25 This in turn would impact the way a society, both at individual and collective levels perceive and experience ideas like ‘change’, ‘progress’ etc. The Western mode of reverence and its perception of ideas related to ‘progress’, though a product of single culture, has become popular and successful in material terms across the globe after colonialism and through modernity & globalization. As a result, along with the categorization of ‘modern’, a category of ‘traditional’ also gets created that it has become a cliché to stereotype the ‘traditional’ as stagnant and regressive old against the ever-changing, progressive new. Indian traditions tend to refresh themselves for the demands of the present, confronting new conditions for self-understanding. In its journey in the Möbius strip on the surface of change, it might take a new ‘neo’ in the future as it has taken in the past several times. Such an exercise has been alive in Indian traditions because of the manner in which they revere their past and their ancestors. In such a case, change and continuity do not appear as binaries; rather they appear complementary to each other.

Endnotes :

- Martin Heidegger, What is called thinking ?, trans. Fred D.Wieck, New York: Harper & Row, 1968, p. 141.

- By ‘West’ what is meant here is not a historical or territorial category, rather an analytical category, which emerges in the enlightenment thought through a self identification of what is ‘West’ & ‘East’, much like identification of ‘oriental’ & ‘occidental’. If we are to define ‘West’ as a historical or territorial category, one has to keep in mind about the multiplicity of traditions, including the pre-Christian or non-Christian traditions of the territorial West, such an endeavor is beyond the concern of this article. On the other hand, by ‘Indian traditions’ what is meant here is about a distinctive culture from the ‘West’, which has continued to survive historically. Though its culture and civilizational limits cannot be territorialized completely, the examples this article bears are taken only from the country that is today identified as India.

- However, one must be aware that many Indians today like many in the rest of the world do perceive subjects like progress, change etc through the lens of ‘modernity’ or from the perspective of ‘West’. Similarly, many people in the West are culturally adapted to the Indian way of thinking. Therefore the attempt here is not to give a mosaic classification between how people belonging to these geographies do think, rather the classification only exists in the form of identifying them as two different traditions.

- Robert King Merton, On the shoulders of Giants: A shandean Postscript, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985,p.1.

- In his words, “We see more and further than our forebears did, not because we have better eyes or because we’re taller, but because we dwarfs are sitting on the shoulders of giants” See in, Aleida Assmann, Is time out of joint?, trans. Sarah Clift, New York: Cornell University Press, 2020, p. 201.

- John of Salisbury, Metalogicon, Book III, Chapter 4. Cfr. Troyan, Scott D., Medieval Rhetoric: A Casebook, London, Routledge, 2004, p. 10.

- Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, “Modern, Modernität, Moderne,” in Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe: Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland, ed. Otto Brunner et al., vol. 4, Stuttgart: Metzler 1978, pp. 93–131. Cited via, Aleida Assmann, Is time out of joint?, trans. Sarah Clift, New York: Cornell University Press, 2020, p. 13.

- A. Assmann, Is Time out of Joint ?, p.14

- By temporal registers what is meant here is the temporal boundaries constructed - past, present and future, or the historically narrated ancient, medieval and modern.

- A. Assmann, Is Time out of Joint ?, p.40. The four prophets (giants) of the Hebrew Bible ( Old Testament) depicted are ; Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel and Daniel and the apostles (dwarfs) are Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. For the adherents of Hebrew Bible (Jews), their Testament isn’t ‘old’ as they don't accept the ‘new’ testament, as they do not consider Jesus as their Messiah, which the ‘dwarfs’ of New Testament claims to be the one about whom the Old Testament prophets spoke about.

- It’s worth remembering that the people of the Old Testament (Jews) call it the Hebrew Bible, as for them a ‘new’ testament is non-existent.

- M.K Gandhi, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing house, 1946.

- Mahadev Desai, trans., The Bhagavadgita According to Gandhi, Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2009, pp. 39-40.

- Vishwa Adluri and Joydeep Bagchee, The Nay Science: A History of German Indology, New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2014, pp. 435-436.

- Gandhi himself describes the classical meaning of Yajna as “...any activity for the good of others… in the spirit of dedication to God. The word Yajña comes from the root ‘yaj’, which means ‘to worship’, and we please God by worshipping Him through physical labour.” See in, Mahadev Desai, trans., The Bhagavadgita According to Gandhi, Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2009, p. 39. It is to be noted that while sacrifice or ‘giving’ is one aspect of Yajna, ‘taking’ what is required is an equally important aspect of it too. This is not to perceive giving and taking as two different acts, rather the idea is to convey that by the act of taking or consuming minimally, simultaneously, an act of giving happens naturally. Such an attitude kept in mind while performing rituals and day to day actions are possible out of Bhakti.

- Adluri and Bagchee, The Nay Science, p. 436.

- Vivek Dhareshwar, ‘Framing the Predicament of Indian Thought: Gandhi, the Gita, and Ethical Action’, An International Journal of the Philosophical Traditions of the East, 22:3, 257-274.

- Makarand Paranjape, Swami Vivekananda: Hinduism and India's Road to Modernity, New Delhi: HarperCollins India, 2019.

- The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, Vol. 6, Calcutta: Advaita Ashram, 1958, pp.279-280.

- Amartya Sen, The Argumentative Indian: Writings on Indian History, Culture and Identity. United Kingdom: Penguin Adult, 2006.

- Mahadev Desai, trans., The Bhagavadgita According to Gandhi, Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2009, p.39.

- ‘Karmaṇyevādhikāraste mā phaleṣu kadācana, mā karmaphalaheturbhūrmā te saṅgo’ stvakarmaṇi’ Bhagavad Gītā 2.47. (English Translation by Swami Chinmayananda Saraswati, Italics in the bracket are added).

- A. Assmann, Is Time out of Joint ?, p. 40.

- Peter Sloterdijk, Infinite Mobilization: Towards a Critique of Political Kinetics, trans, Sandra Berjan, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2020, pp.1-3.

- Reinhart Koselleck, Futures Past: On the Semantics of Historical Time, trans. Keith Tribe, New York: Columbia University Press, 2004. Though we associate history with the past alone, Reinhart Koselleck illustrates how the notion of the future determines the way cultures look at their past.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: Wikipedia

An amazing read. Thanks for sharing your thoughts with us.

Post new comment