The China-Japan Bilateral Relationship has had an enduring impact on international relations. Usually territorial disputes, conflicting political interactions, anticipated military conflicts are all associated with reduced trade flows and states with similar political interests tend to trade more with each other than with other states. In this regard, the coexistence of political hostilities and an extensive economic engagement confound the reading on the China-Japan relationship. Since both countries are intimately connected—economically and politically—with the United States, the implications of the China-Japan relationship go far beyond the purview of their bilateral relations. There has been significant Chinese backlash after the recent renaming by Japan's Ishigaki City Assembly of the administrative region containing the Senkaku Islands on June 22. The Coronavirus Pandemic has also disrupted a major summit between their leadership that would have reset the contours of bilateral cooperation to include larger global issues. The long-anticipated President Xi’s State Visit to Japan has essentially floundered. Initially set to have been in March and later postponed to the fall; the summit preparations have now been altogether halted for this year.

In late May, two foreign policy panels of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party submitted a resolution to the government urging it to carefully reconsider whether the visit should go ahead in view of China's controversial security bill for Hong Kong1. Around the same time, US President Trump proposed hosting an expanded G7 summit by inviting India, Australia, South Korea, and Russia, (now scheduled for September) that clearly is meant to counter China. This has made the Japanese position untenable as receiving Xi as a state guest around the time it participates in a US-chaired G7 gathering will make it difficult to accommodate either the American or the Chinese side. While there is talk of Abe and Xi meeting on the fringes of G20 meeting in Saudi Arabia in November, the prevailing view within the Japanese government is that it is likely to take a few months to make necessary preparations and thus Xi’s visit will not come until early next year or later2. Xi’s visit to Japan, a first by a Chinese President in more than a decade would have been marked by the release of a fifth political document that would have underscored the shift in relationship focus from mutual benefits to cooperation on global issues.

The earlier four political documents have been the 1972 Joint Communique, 1978 Sino-Japanese Peace and Friendship Treaty, 1998 Japan-China Joint Declaration on Building a Partnership of Friendship and Cooperation for Peace and Development and 2008 Joint Statement on Comprehensive Promotion of a Mutually Beneficial Relationship Based on Common Strategic Interests. The irony to note is that this summit would still have been marred by increased military incursions from China that have seen a rapid year-on-year increase in the waters around the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands. Chinese ships have been spotted in the area for more than 70 consecutive days this year, the longest since September 20123. Studies have long shown that a pipeline from the East China Sea to the Japanese mainland would be expensive and technologically intimidating because of the distance and the two thousand meter plunge the ocean floor takes at the Okinawa Trough4. Infact, in the 1980s after the discovery of the Pinghu oil and gas field, Japan co-financed two oil and gas pipelines running from the Pinghu field to Shanghai and the Ningbo onshore terminal on the Chinese mainland through the Asian Development Bank and Japanese Bank of International Cooperation.

Thus, after a series of confidence building measures in the early 2000s, the 2008 agreement mooted the joint development of resources by China and Japan in East China Sea. The landmark visit by Abe to China in 2018 during the 40th Anniversary of the peace and cooperation treaty also saw the establishment of communication protocols aimed at preventing accidental military clashes in East China Sea and agreement on holding the First Annual Meeting of the Aerial and Communication Mechanism later that year. There was also the conclusion of the Japan-China Maritime Search and Rescue (SAR) Agreement. Yet during the same summit, regarding the issue of the East China Sea, Prime Minister Abe once again conveyed Japan's understanding of the issue based on the recognition that there will be no genuine improvement in the Japan-China relationship without stability in the East China Sea5. What is also important to note is that earlier in March 2018, a Japanese Amphibious Rapid Deployment Brigade, on the pattern of US Marines, was created with a mandate to defend — and if necessary, retake — Japanese islands that could be target of invasions.

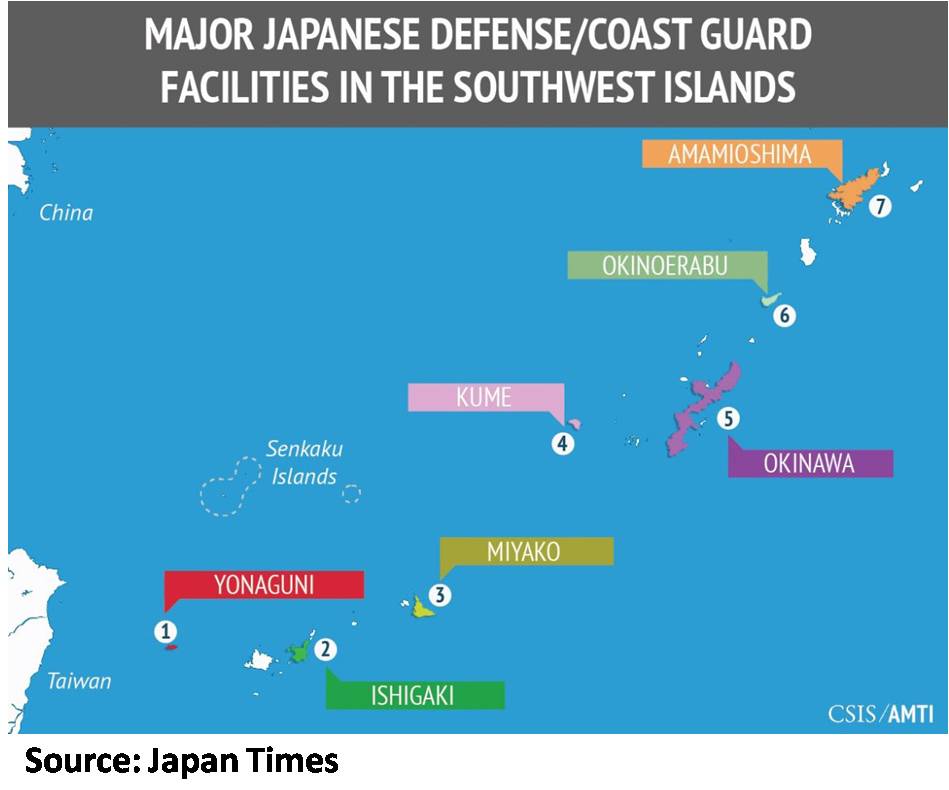

This is what makes the China-Japan relationship profoundly confounding. There are elements of cooperation interspersed in the outright rivalry between the two countries. In past few years, there has been a rapid expansion of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces’ presence across the “first island chain” in what is referred to as the “south western wall defence” strategy. The string of Japanese islands that stretch between Kyushu and Taiwan are part of the “first island chain” that Japan sees as crucial for containing military threats and preserving its sovereignty. Legal measures put in place in 1977 restricted uninhibited foreign maritime traffic to only five of Japan’s many straits: Soya, Tsugaru, Tsushima East, Tsushima West and Osumi. In many ways, this was sufficient before continental powers were capable of projecting to the broader Pacific Ocean. But those circumstances have changed, and China has actively started challenging Japanese sovereignty in the East China Sea. For Japan, it is not just the Senkaku Islands, but also the Tokara Strait and the Miyako Strait that do not get much spotlight that are the biggest trouble spots6.

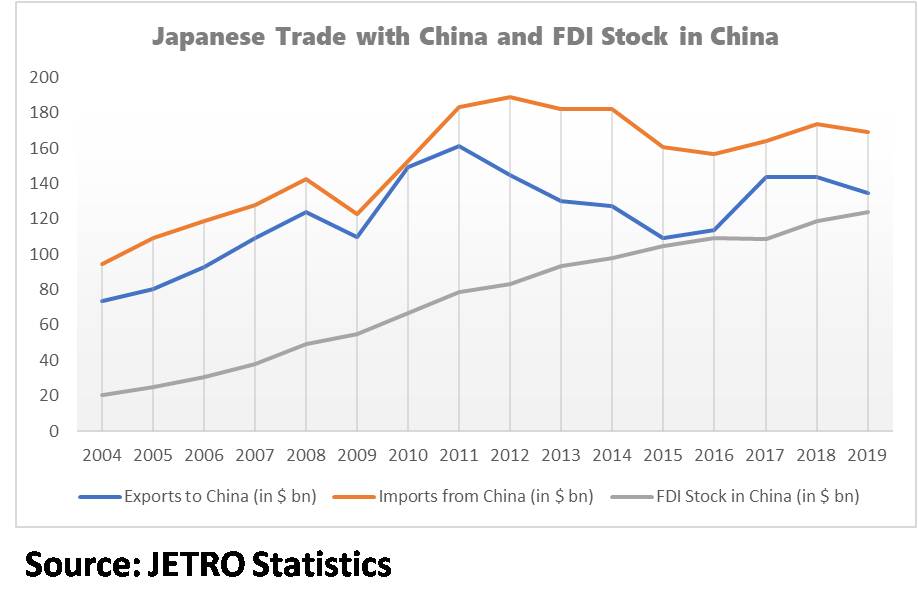

The economic devastation brought by the pandemic has both questioned and reemphasized the rationale behind the large economic content in the bilateral relationship. China remains a major economic opportunity for Japan owing to China's large market size and technological expertise, while systemic issues of aging demography, deflation, under-competitiveness of Japanese banks etc. continue to plague the Japanese economy. Japanese financial institutions, including megabanks, have combined lending of more than 7 trillion yen ($63.57 billion) in China, as Japan’s negative interest rates and dwindling population lead them to pursue larger business overseas7. In the last decade, China has also come to play an expanded role in Japanese supply chains. Japan relies on China for 21.1% of its imports of intermediate goods, according to the Japanese government. A total of 37% of auto parts shipped to Japan last year came from China8. Beijing, on the other hand, which is trying to fend off US attacks and reduce the country's reliance on American companies for high tech devices, sees Japan as a lucrative source of high-end technologies.

The Coronavirus Pandemic has not been the first instance of disruption of supply chains in Japan that sees recurrent natural disasters. However, the difference between a natural disaster and pandemic has been the degree of uncertainty regarding resumption of full economic activity. This uncertainty has been further compounded by the rapid deterioration in US-China ties, and consequent slump in Japanese exports. There had been a visible slowdown in the Chinese economy even before the pandemic as the 2016 credit binge tapered off, with many global financial watchdogs issuing warnings on a possible banking crisis in China9. On the other hand, Japanese corporates retained earnings stood at record-breaking level of about 130 per cent of gross domestic product at the end of 201910. This huge accumulation of rainy-day savings puts Japan in an advantageous position as it can seek new markets for growth. The EU and Japan's Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) entered into force on 1 February 2019. This year, there are also expectations that the Japanese-supported Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP or TPP-11) will expand to bring in new members.

Thus, the pandemic has led Japan to double down on economic concerns emanating from China. In April, Japan’s Cabinet earmarked 248.6 billion yen ($2.33 billion) for subsidies to businesses that move production back to Japan, covering up to two-thirds of relocation costs. The same month, Japan's National Security Council established a dedicated economic team after an acknowledgment last year of the growing importance of economic issues in national security thinking. A Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry (METI) senior official was appointed to a new post within the council's leadership, giving the ministry representation in a body previously dominated by the foreign and defence ministries. In June, the Japanese Ministry of Finance issued new regulations that mandated advance government approval for a foreign investor to take a stake of 1% or more in any Japanese enterprise in 12 "core" strategic sectors, from defense to utilities. Previously, foreign investors did not require pre-screening unless taking stakes of 10% or more in strategic companies11. Also, even before the pandemic, Japan had been pursuing China to end forced technology transfers, enforce protection of trade secrets and crack down on pirated products. Japan and China held the First Japan-China Innovation Cooperation Dialogue in Beijing in April 2019.

Yet, a government aid of $2 billion is going to be insufficient to make a dent to Japanese FDI stock of $124 billion in China. The Japanese have been running businesses in China with well-established network of relationships or ‘Guanxi’ that go beyond government to government ties. “Toyota has no plans to change our strategy in China or Asia due to the current situation,” the Aichi-based carmaker said in a statement around mid-May. “The auto industry uses a lot of suppliers and operates a vast supply chain and it would be impossible to just switch in an instant. We understand the government’s position, but we have no plans to change our production12.” Later in June, Toyota Motor announced a joint venture with five Chinese companies to develop fuel cell systems for commercial vehicles, positioning itself to cash in on China's ambition for the zero-emission automobiles13. But in other areas such as communications technology, Japan seeks to directly compete with China. In the "Beyond 5G" strategy released in April, Japanese government unveiled its ambitions to capture a 30% global market share for base stations and other infrastructure, up from just 2% at present. Tokyo also wants 10% of relevant patents worldwide to come from Japanese companies14.

The role of economic growth providing legitimacy to East Asian governments is heavily understated in the analysis on the region. When China had unilaterally declared an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the islands in East China Sea in late 2013, two days later (on November 25) China and Japan along with South Korea sat down to discuss a trilateral free-trade agreement as per schedule15. The two countries have a subtle but intense rivalry for power influence in the region. Both lead their own economic and defense initiatives such as the Asian Development Bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, Expanded Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, the Belt and Road Initiative, Vientiane Vision etc. Further, Japan plays a strong participatory role in nearly all anti-China narratives and initiatives be it the Indo-Pacific, Quad, D10, Expanded G7, Inter Parliamentary Alliance on China etc. At some places, where their threat perceptions might match such as on North Korea, China and Japan take different approaches. Yet one cannot deny the political trends that lead both leaderships to pursue better ties, or at least conflict-free ties. In 2019, Xi Jinping deputed close ally and Vice President Wang Qishan to look after China’s ties with Japan.

Overall, China-Japan ties have their own long-standing internal dichotomies of conflict and cooperation that is unlikely to change. It is not a simple transactional relationship but a multi-dimensional relationship where America’s security commitments to Japan overlap with Chinese ambitions for regional hegemony. Thus, the role of the United States in their bilateral relationship has a larger than estimated impact. Thus, if a second Trump administration stringently pursues stationing of US land missiles or decoupling of American supply chains from China, Japan would show responsive support accordingly. As the world emerges from the pandemic, and the US Presidential elections in November, one would be able to make a clearer prognosis for the future of China-Japan relations. But even then, reading the tea leaves on this bilateral relationship remains a humungous task.

Endnotes:

- Xi's Japan trip unlikely this year as US-China tensions burn, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Inside-Japanese-politics/Xi-s-Japan-trip-unlikely-this-year-as-US-China-tensions-burn

- Japan unlikely to fix date soon for delayed state visit by China’s Xi Jinping, https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/east-asia/article/3087822/japan-unlikely-fix-date-soon-delayed-state-visit-chinas-xi

- Japan city vows to rename disputed isles area, irking China, Taiwan, https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20200622/p2g/00m/0na/078000c

- Disputed Claims in the East China Sea, https://www.nbr.org/publication/disputed-claims-in-the-east-china-sea/

- Prime Minister Abe Visits China, https://www.mofa.go.jp/a_o/c_m1/cn/page3e_000958.html

- Understanding Japan's southwest islands buildup, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/opinion/2019/04/22/commentary/japan-commentary/understanding-japans-southwest-islands-buildup/#.XuzuE2gzbIU

- Japan Conducts Emergency Survey On Its Banks Amid China Virus Outbreak: Sources, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-health-japan-banks/japan-conducts-emergency-survey-on-its-banks-amid-china-virus-outbreak-sources-idUSKBN20D0R2

- Japan scouts more Asian players for TPP to cut China dependence, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Japan-scouts-more-Asian-players-for-TPP-to-cut-China-dependence

- China's credit binge increases risk of banking crisis, says watchdog, https://www.theguardian.com/business/2016/sep/18/central-bankers-group-bis-stark-warning-world-economy

- Coronavirus shows the value of Japan Inc’s cash piles, https://www.ft.com/content/e15f9572-6803-11ea-a3c9-1fe6fedcca75

- Japan names 518 companies subject to tighter foreign ownership rules, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Markets/Japan-names-518-companies-subject-to-tighter-foreign-ownership-rules

- Leave China? No thanks, some Japanese firms say to Tokyo’s cash incentives, https://www.scmp.com/week-asia/economics/article/3083988/leave-china-no-thanks-some-japanese-firms-say-tokyos-cash

- Toyota takes off for fuel cell age with Chinese carmakers, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Automobiles/Toyota-takes-off-for-fuel-cell-age-with-Chinese-carmakers

- Race For 6G, https://asia.nikkei.com/Business/Technology/Race-for-6G-South-Korea-and-China-off-to-early-leads

- Michael Ivanovitvh, “China and Japan trading goods and war threats”, Dec 29, 2013 at http://www.cnbc.com/id/101300548.

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

Image Source: https://image.cnbcfm.com/api/v1/image/104881314-GettyImages-874192418.jpg?v=1540531659&w=740&h=416

Post new comment