Introduction

South Asia was earlier as identified as Indian Sub-continent. Generally, it was identified as ‘India’ under the British Empire. 94 percent of what territorially constitutes South Asia today was governed by the British (Guneratne & Weiss, 2014). Thus this part derives its coherence partly to the colonial past. It was the period around the World War II that the world was divided into various parts by the academia in US. It had a political undertone to it, as it was driven by the rise of the US as a superpower and the competition it was facing from Soviet Union (ibid). The reason behind grouping the states of South Asia into a single category was a result of the common cultural identity they shared. The common past and the colonial legacy.

Arjun Guneratne and Anita M. Weiss argue that, “one way to think about the politics of modern South Asia is to ask how the institutions and political forms that the region inherited from British rule have fared in decade since. None of the modern states predate the British (although nationalists would differ); the political unity that each represents (with exception of Nepal) is a “legacy of the Empire” (Guneratne & Weiss, 2014, p. 7). Lot of what South Asia inherited from the colonial past, haunt it even today. There has been a shadow of British colonialism in the evolution of the South Asian region. South Asia, thanks to colonial history, had to adopt certain concepts like sovereignty, nation state, borders and political organization. All of these were alien to South Asia. These concepts in western world was the result of the end of conflicts, while in South Asia they were reason of many conflicts which ultimately hindered regional consciousness and integration. Perceptions about each other changed as old historical narratives were replaced by exclusive, imagined and sponsored histories, often categorized in terms of ‘us’ and ‘them’.

This paper deals with the four rudimentary colonial legacies which have been the reasons for lack of trust among states in South Asia and have apparently sabotaged regional integration in the region. Colonial cartography, the very idea of nation-states accompanied by borders and the inheritance of military and civil bureaucracy, all of which were emulated in South Asia, proved to be incompatible. They have been discussed in detail under separate headings as under.

Cartography: An initial Tool towards Colonialism

Cartography becomes an important discussion because it can be considered as a seed for colonial legacies. It was cartography that led to borders and followed by the notion of sovereignty and nation-states. According to Kalpagam, surveying and mapping were the initial tools towards a colonization project (Kalpagam, 1995). It was necessary for them to carve out a plan to reap economic and political benefits out of colonies. Mapping and surveying served their interest; these were required in order to bring more and more territories in their control, and this in turn led to simultaneous rise in revenue generation (Ramchandraiah, 1995). Cartographic representation also brought with it certain images of the foreign territory which helped them to justify their ideologically driven imperial project.

Cartography included surveying and mapping, but what mattered more was how the map is projected - the color of the map, representation of the relief features and the symbols used. Not all maps are innocent portrayal of geography. Harley asserts that maps not only presented the geographical knowledge but it also justified the cultural superiority of the Europeans (Harley, 1989). Cartography was used as a tool by colonial powers to justify their expansionist policies and assert their domination.

From Frontiers to Borders: Problematizing the Transition

To deal with any dispute, one has to decipher the nature of the dispute first and the role of political discourse in shaping the trajectory of that dispute. There is no doubt that the colonial modernity brought progress to this part of the world. At the same time, this region was forced to adopt things that were alien and unsuitable. The inter-state and intra-state boundaries drawn by the British have precipitated in the form of limited and full scale war between the countries of South Asia and beyond. India and Pakistan were against each other in the battle front thrice as a result of territorial disputes, and the same has been the case between India and China. Colonialism has been the root cause of the intractable territorial boundary disputes in South Asia and these continue to haunt even today. To satisfy their parochial interest of harnessing maximum revenue, the colonizers deliberately overlooked the socio-cultural, linguistic and religious complexities of the region. Mishra argues that, “the basic problems of South Asian borders is that they are artificial and they separated local community who had long history of togetherness” (Mishra, 2016, p. 19).

The fuzzy and complex demarcation of territory was posing a challenge to the British to administer efficiently. With the transfer of the reigns from the East India Company to the British Crown, ‘new territoriality’ (ibid) came into force. They divided the sub-continent into different political units governed by one center. This was a kind of imposition; there were socio-cultural units which were divided and there were also the cases of merging of two or more socio-cultural units into one. The notion of sovereignty, which was a western concept, was also imposed on South Asia by the British. The notion of sovereignty in South Asia was a traditional one based on the charisma of the authority (ibid). Traditionally, there was no concept of border, rather the frontiers defined the reach of a political kingdom. Frontiers were loose demarcation, they were kind of grey area and marked the political reach of a kingdom. As one moved away from the center, the political clout and reach of the kingdom diminished.

Transition from frontier to border was a result of the colonial modernity. Cartography can be said to be the vanguard of colonial project. In order to divide the world into colonies, suzerains and protectorates, the concept of border proved to be very fruitful for them. The problem is not about the border per se, but about how the borders were demarcated (ibid). Natives were never taken into consideration in the whole project; had that been a case, the issue of borders would not have been this problematic.

There were two models of nationalism prevalent during the period of colonialism. One that was called European model, which was based on ethnicity, identity, language, religion and cultural homogeneity (Gellner, 2006). The other was premised upon the historical and cultural antecedents pervasive in the Indian sub-continent dating back to ancient times and in the form a common front against the colonialism (ibid). The British came up with the policy of ‘divide and rule’ based on the former form of nationalism in order to bring schisms into the potent common anti-colonial struggle in the sub-continent (Mishra, 2016).

Notwithstanding the latter model of nationalism, the British fuelled the flame accepting the ‘two-nation theory’ and thus subscribing to the Muslim League’s demand of a separate country (ibid). Consequently, this turned out to be a major bone of contention between India and Pakistan, reverberations of which are quite discernible even today. There are issues regarding the demarcation of the border which still have a significant bearing on the issue of regional integration in South Asia. The issue of Kashmir remains unsolved till date, Pakistan claims that Kashmir belongs to it on the basis of religious commonness (Dash, 2014; Jalal, 1995). The Partition of Bengal in 1905 into two parts was on religious line to weaken the freedom struggle, as Bengal used to be the powerful hub of freedom movement. This acted as a blueprint for the Radcliffe Commission appointed in 1947 to deal with the task of demarcating a border between India and Western Pakistan and India and Eastern Pakistan. All this Commission did was to divide the Hindu and Muslim population into two countries. Sir Cyril Radcliffe was a law professor and had no knowledge about the geography and cultural of South Asia. The demarcations were so absurd that even certain village units were divided and cases of a single house being divided were also evident (Mishra, 2016).

Border issues with China has also manifested in the form of conflict. In the Shimla Accord of 1914, where the signatories were China, Tibet and British India, border between India and Tibet was finalized and named as McMahon Line (Dash, 2014). After independence, India considered the McMahon Line as a legitimate border, while China out-rightly rejected that consideration. China contested saying that the border at that time was drawn through unequal accord when the British were too powerful and forced the agreement on unequal terms.

Obsession with Sovereignty

Understanding of sovereignty has changed over time, it can be better understood by disaggregating it into its key element- autonomy, control and legitimacy (Mattli, 2000). Regional integration requires ‘sovereignty bargains’, which has been described by Karen Litfin as acceptance of certain limitations in order to reap certain benefits but this does not mean that the state is ceding its sovereignty altogether (ibid). There may be instances where more control may come at the cost of decreased legitimacy. In case of a country participating in an international environmental regime, there can be some sacrifice in autonomy but at the same time the external legitimacy of the country also increases. Thus, there is a need for a broader understanding of the term ‘sovereignty’.

Pratap Bhanu Mehta argues that the understanding of sovereignty, in case of South Asia is parochially trapped under this whole notion of ‘autonomy’ (ibid). This can be attributed to post-colonial syndrome that has made the states in South Asia paranoid of the presence of powerful India in the neighborhood. The British Empire, in order to secure its imperial interests, went on to annex some territories of the Kingdom of Nepal, tried their hand in Afghanistan but suffered a major setback, and took Sri Lanka under their control. The colonial empire did not respect the sovereignty of the neighboring territories. Thus, being relatively bigger in size and power India is seen as a threat to their autonomy by other states in South Asia (Nandy, 2006). Notwithstanding that India may not be having any implicit and explicit desires of dominating the region, the mere possibility of it generates defensive response from other countries.

This fear widens the trust-deficit and inhibits friendly relations between India and other states in South Asia. Opposition to free trade by most of the countries, where Sri Lanka and India being the outliers, had a debilitating impact on their economy itself. Territorial disputes among the South Asian countries remain unresolved till date. These are inextricably linked to the lack of political will among the states towards regional integration. One can trace the trajectory of these disputes to the colonial times

Nation-state: Emulation not Evolution

The very process of nation-building in South Asia was an imposition of the western values. This part of the world was forced to relinquish its traditional value. Nationalism of this sort ignored the primordial identities. Tagore and Iqbal have criticized the western notion of nationalism and the accompanying concept of nation-state as a reason for present day fissures in South Asia (Mishra, 2014). Nations in South Asia failed to accommodate the problem of multiple ethnicity, and thus incapable of articulating a common identity. By virtue of it being an alien concept and something that was an outcome of emulation not evolution.

Nation-states in South Asia was an artificial creation (Nandy, 2006; Mishra, 2014), thus the onus to manage this newcomer was on the political system of the respective country. The notion of nation-state and nationalism in South Asia was transported through imperial channels but subsequent inability of the leadership to bring out the modified version of it, which could synchronize with the rich tradition prevalent in the region was a major drawback (Mishra, 2014). The leaders of the freedom movement adopted the territorial connotation of nation-state based on statist premise, unchecked from the colonizers: ‘The alleged failure of South Asia political systems in articulating an all-inclusive nationalism is not due to them being illegitimate or artificial, but because of the attempt to develop nation-states in the region on the basis of homogeneity in line with Western Europe’. (Mishra, 2014, p. 82)

Political system in this part of the world instead of celebrating the primordial identities, tried to assimilate it and sometimes even by coercive measures. States used processes like federalism and arbitration as a positive measure to assimilate these identities. Contrary to these measures were the coercive one which included ethnic cleansing and genocide. Most of these processes have been applied in different part of South Asia but needless to say, they have only exacerbated the problem instead. Ethnic conflict in case of Sri Lanka, federation as a tool was applied in India and Nepal, the continued systemic violence against the Chakmas in Bangladesh epitomize the above case in context of South Asia.

The very obsession with the territorial notion of nation state in South Asia has led to a common understanding even among the intelligentsia that nation states are bound to have a unique and different culture (Nandy, 2006). No two nation state can have a common culture. Nandy argues that it is because of the above reason that any attempts of secessionism and autonomy are dealt with brutal measures. The common heritage which forms the backbone of the oneness of the region is perceived as an existential threat to the nation state by state apparatus. Nandy formulates South Asia as “a collective of reluctant state” (ibid, p.541). Forget about the common heritage, nation states in this region define themselves “not by what they are, but by what they are not” (ibid). Just for the sake of example, Pakistan defines itself avoiding being India. Interestingly, South Asia has many commonalities, the most promising is their common cultural foundation, the Indic civilization. But ironically, the states in the wake of defining themselves as different and autonomous from others deliberately relegate this commonality.

Bureaucratic Culture: Implications for the Post-colonial South Asia

Administrative system in most of the South Asian countries are the legacy of the colonial period. Bureaucratic models were adopted in South Asia without putting them into litmus test of the contextual realities and historical antecedents (Haque, 1997). The attributes that can be ascribed to the bureaucracy of the British, namely centralization, rigidity, elitism, secrecy were very much a part of the post-colonial states in South Asia (ibid). Bureaucratic elites were the result of nurturing of the colonial education and they became a convenient tool to preserve the colonial legacy in the region (Tejani, 2014).

There was a large gap in terms of the contact between the common masses and the civil servants, while they were supposed to be public servants. The top-down hierarchy of this bureaucratic culture made them feel superior to common people. A potent challenge to the bureaucratic system came from the pro-market reforms that includes privatization, liberalization and deregulation. However, this was delimited to only its size and scope (Haque, 1997). While the structure, norms and influence of the bureaucracy remained the same.

The bureaucratic structure in the post-colonial period was overdeveloped compared to other political institutions which were just at their embryonic stage (Jabeen & Jadoon, 2013). Bureaucratic modernization resulted in weak political structures and limited political participation which often led to military dominance and even military rule in some countries. The colonial rule had marginalized politics in the past and continually discouraged the checks and balance over the bureaucracy by the political institutions. The sub-ordination of the political apparatus and the resultant political vacuum gave leeway to the civil and military bureaucracy. This gave rise to the new powerful ‘bureaucratic-military oligarchy’ (Alavi, 1972).

The military and bureaucracy were tools of colonial powers and were employed to suppress the freedom movement rendering them on the opposite side of politics and the political leadership of the freedom movement (Haque, 1997). But after independence both had to work along with each other. Already institutionalized procedures which gave bureaucracy an edge over the politician coupled with the direct connection of the bureaucracy with the common masses, left the politicians with the role of a mere moderator between the bureaucracy and people (Alavi, 1972).

Military-bureaucratic oligarchy has enjoyed enormous power, they played a significant role in making governments. It was in the military coup in 1958 that General Ayub Khan got the reign of Pakistan by abolishing the parliamentary government. Though later on he recognized that a constitutional government was needed in supplementary role and thus brought forth the system of ‘Basic Democracy’ (ibid). Hamza Alavi argues, “…… it would be simplistic to take for granted that the bureaucratic-military oligarchy necessarily prefers to rule directly in its own name. It often prefers to rule through politicians so long as the latter do not impinge upon its own relative autonomy and power” (ibid, p.53).

Pakistan state failed to establish a democratic system, which gave space to military to assume leadership role in the state. They continued to create a fear of the Indian threat among common public in Pakistan, helping them fasten their control over the state. They ignored the fact the major threat to the stability of their state will emanate from within. Military has had a preponderant role in strategic affairs and governance within the country. Military has always tried to stall and sabotage any process aimed at bringing amicable solution to the rift between India and Pakistan. They have tried to destabilize the Indian state by supporting separatists in Punjab and Kashmir and also promoting terrorism in their soil against India. Similarly, the lack of institutionalization of democracy in Bangladesh has also made the military quite powerful.

Conclusion

Colonial legacy, in case of South Asia, has been a major reason for the lack of trust among states, strong military presence, and huge investment in defense, instability in political regimes in states and powerful bureaucracy. Together this has emerged out as hurdles in the regional integration. It was cartography which was the basic tool towards colonialism. Cartography brought with it borders, which led to the formation of states. The legitimacy of the states depended upon the sovereignty; constant fear from the neighbors and the memory of the intervention of the alien rule in the form of colonialism made the nation-states in South Asia obsessed with territorial notion of sovereignty. Despite of the fact that sovereignty trade-offs can turn out to be favorable in the long run, the states in South Asia rarely took step to compromise with the sovereignty.

Bibliography

- Alavi, H., 1972. The state in post-colonial societies Pakistan and Bangladesh. New Left Review, 1(74), pp. 50-70.

- Burnett, D. G., 2001. Masters of All They Surveyed: Exploration, Geography, and a British El Dorado. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Chandra, V., 2015. Introduction. In: V. Chandra, ed. India and South Asia: Exploring Regional Perceptions. New Delhi: Pentagon Press, pp. xxiii-xlvii.

- Dash, P., 2014. Regional Conflicts in South Asia and Their Impact on Regional Integration. European Academic Research, 11(2), pp. 344-3467.

- Gellner, E., 2006. Nations and Nationalism. 2nd ed. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Guneratne, A. & Weiss, A. M., 2014. Introduction: Situating Domestic Politics in South Asia. In: A. Guneratne & A. M. Weiss, eds. Pathways to Power: The Domestic Politics of South Asia. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, pp. 1-20.

- Haque, M. S., 1997. Incongruity Between Bureaucracy And Society In Developing Nations: A Critique. Peace & Change, 22(4), pp. 432-462.

- Harley, J., 1989. Deconstructing the Map. Cartographica, pp. 1-20.

- Jabeen, N. & Jadoon, M. J. I., 2013. Civil Service System and Reforms in Pakistan. In: Public Administration in South Asia. London: Taylor and Francis , pp. 453-470.

- Jalal, A., 1995. Democracy and authoritarianism in South Asia: A comparative and historical perspective. 1st ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kalpagam, U., 1995. Cartography in Colonial India. Economic and Political Weekly, pp. 87-98.

- Mattli, W., 2000. Sovereignty Bargains and Regional Integration. International Studies Review, 2(2), pp. 149-180.

- Mehta, P. B., 2012. SAARC and sovreignty bargain. In: K. M. Dixit, ed. The Southasian Sensibility: A Himalayan Reader. Delhi: Sage Publications, pp. 189-197.

- Mishra, B., 2014. The Nation State Problematic in Asia: the South Asian Experience. Perceptions, 19(1), pp. 71-85.

- Mishra, S., 2016. The Colonial Origins of Disputes in South Asia. The Journal of Territorial and Maritime Studies, 3(1), pp. 5-23.

- Moxham, R., 2002. The Great Hedge of India: The Search for the Living Barrier that Divided a Nation. London: Robinson.

- Nandy, A., 2006. The Idea of South Asia: a personal note on post-Bandung blues. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies, 6(4), pp. 541-545.

- Pennycook, A., 1998. English and the Discourses of Colonialism. London: Routledge.

- Ramchandraiah, C., 1995. Colonialism and Geography. Economic and Political Weekly, pp. 2523-2524.

- Tejani, S., 2014. The Colonial Legacy. In: A. Guneratne & A. M. Weiss, eds. Pathways to Power: The Domestic Politics to Power. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan, pp. 21-75.

(Ajay Pratap Singh & Vivek Sugandh are Research Scholars, Centre for Russian and Central Asian Studies (CRCAS), School of International Studies, JNU)

(The paper is the author’s individual scholastic articulation. The author certifies that the article/paper is original in content, unpublished and it has not been submitted for publication/web upload elsewhere, and that the facts and figures quoted are duly referenced, as needed, and are believed to be correct). (The paper does not necessarily represent the organisational stance... More >>

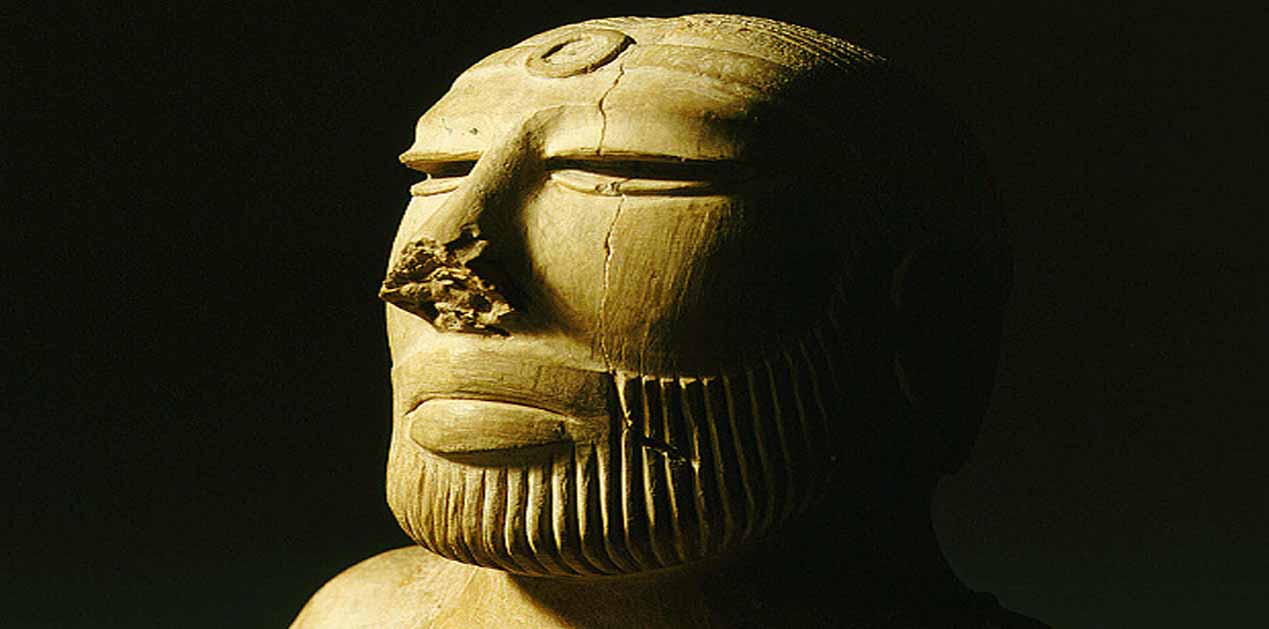

Image Source: https://secure.i.telegraph.co.uk/multimedia/archive/03269/Harappan-Indus_1_3269002b.jpg

Great work

Post new comment