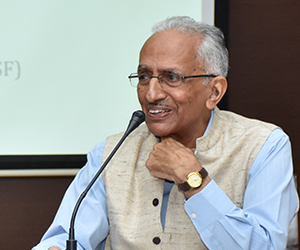

Kanwar Pal Singh Gill has been hailed as one of the most successful fighters against terrorism. He vanquished what was one of the most lethal and one of the most devastating terrorist movements in the history of the world. He has also been criticized as a terrible violator of human rights, a man who had no respect for life and was very brutal in his methods. What was the truth? To arrive at that, it would be necessary to understand the situation that prevailed in the Punjab those days.

Siddharth Shankar Ray, then Governor of Punjab, in a report dated 11 May 1987 to the President of India, said that “ever since the new fundamentalist movement commenced…the situation began getting out of hand to such an extent that from about the middle of April 1987 there was not only a parallel authority working in the state by the fundamentalists and/or the extremists in the temple and the gurudwaras.. but terror stalked the land and fear abided in almost every heart.” The Governor went on the say that the state government’s writ has “ceased running in large areas of the state, particularly in almost all rural areas”. The terrorist movement took a qualitative leap in the late eighties with the acquisition of Kalashnikov rifles by the terrorists, thanks to Pakistan fishing in the troubled waters. There were political assassinations and brazen attacks on security forces. The Indian Army was not spared; there was a daring attack on an Army convoy in Taran Taran on 23 October 1990. The civil administration was paralysed. Judiciary was overawed. Terrorists prescribed school uniform for boys and girls: boys were to wear black trousers, white shirt and kesari turban and the girls were to wear black salwar, white shirt and kesari dupatta. The singing of national anthem was banned and so was the teaching of Hindi in schools. “In today’s Punjab the militant’s word is law”, bemoaned a writer.

It was against this background that KPS Gill, an IPS officer of Assam cadre, was asked to head the Punjab Police. It was a frightening scenario. Gill rose to the occasion and gave a stellar account of himself. Soon after taking charge as Director General of Punjab Police, he was called upon to lead the Operation Black Thunder in May 1988. The Golden Temple was cleared of terrorists in a clean operation under the full glare of media. In all, 30 terrorists were killed and 199 surrendered. The National Security Guard, which spearheaded the operation or the Punjab Police did not suffer any casualties.

Gill went hammer and tongs against terrorists in the hinterland. It must be mentioned here that his work was facilitated by JF Ribeiro, his predecessor, who had done a lot to restore the confidence of the Punjab Police. Gill’s methods were different. Ribeiro generally followed the letter of the law. At one stage, he is reported to have talked of “bullet for bullet”, though later on he denied having said so. Gill’s methods were unconventional. He perhaps looked upon the terrorists as asuras who had to be destroyed in the best tradition of good prevailing over evil. No quarters were given, no quarters were asked for. Terrorist violence was matched by fierce police onslaught. Human shields were used at several places with supporters or sympathisers of terrorists being asked to accompany security forces personnel in their vehicles. At one stage, when the terrorists started attacking the families of policemen, the Punjab Police gave them a taste of their own medicine. Operation Night Dominance was a unique concept. Normally, security forces dominate during day while terrorists rule by night. During this Operation, the Punjab Police fanned out during night time and established its authority from sunset to sunrise also. The tactics worked. The terrorists loved to hate Gill.

Not that others’ contribution was insignificant. The Border Security Force raised fencing across the border and made any infiltration or exfiltration across the border an extremely hazardous proposition. The CRPF lent valuable assistance to the Punjab Police. The Indian Army made its significant contribution. General OP Malhotra, as Governor, did extremely well. Political support, particularly when Beant Singh was Chief Minister, contributed in no small measure to the success of the anti-terror operations.

KPS Gill, however, stood out as the one man who symbolised the might of the Indian State. But for his relentless campaigns and his success in breaking the backbone of the terrorist movement, the history of India might have taken an adverse turn. The terrorist movement, aided and fuelled by Pakistan, was comprehensively defeated.

It is true that Gill and his men technically violated human rights. After peace was restored in the state, about 2,500 writ petitions were filed in the Supreme Court and the Punjab and Haryana High Courts against Punjab Police officers by individuals and human right organizations. About 120 police officers including six Superintendents of Police faced prosecution. Shekhar Gupta raised some pertinent questions in the Indian Express of 20 August 1996 in this context:

It is perfectly valid to question the methods used by the security forces, but isn’t it more important to ask who is ordering them to do so? It is incredibly and shamefully low of us to ask our armed forces to put their lives on the line, do the dirty work and then, when all is back to normal and the debris of war is cremated or buried, to hark back to the ‘law is supreme in a civil society’ mode..”

The Punjab crisis saw five Prime Ministers and as many Internal Security Ministers. The political class and all the senior bureaucrats in Delhi knew what was happening in Punjab. In fact, the methods being used by the Punjab Police had their tacit approval. It would be unfair, under the circumstances, to fault the police only for the way terrorism was fought. Arun Shourie also deplored the “double standards” of the human rights organisations and the courts and wondered “why should anyone risk his life the next time the country is in peril when this is what he is to get in return?”

Gill had a multi-faceted personality. He was fond of English literature and loved Urdu poetry. Post-retirement, his services were utilised by Gujarat and Chhattisgarh governments as security Advisor.

It is a great pity that KPS Gill was given Padmashri only. Paper tigers and pen-pushers have managed to get much higher awards. Here was a man who challenged Death, risked his life day after day and yet his work and contribution were not adequately recognised. A minor incident of misdemeanour was blown out of proportions to shut the door for higher opportunities and honour to a lion-hearted son of India.

(The writer was Inspector General/Additional DG BSF, Punjab Frontier from 1987 to 1991)

Image Source: http://indianexpress.com

Post new comment