It was, if I recollect correctly, towards the end of 2002. Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee had arrived in Goa to usher in the New Year. I was then located in the State. Having taken a break from journalism a few months before, I had assumed charge as Media Advisor to Chief Minister Manohar Parrikar, and was deputed concurrently as Director of the Government’s Department of Information & Publicity (DIP). It thus became my lot to herd the local media personnel for a photo-op, made possible by Parrikar’s intervention, with the Prime Minister at a sprawling beach resort where the latter had anchored for the New Year.

Some two dozen media persons landed just off the beach. The Prime Minister was out in the open with his entourage, facing the sea at a stone’s throw away, with the muffled sound of waves giving almost the feel of a lullaby. It was a pleasant day and there was cheer all around. Security personnel had semi-circled the spot where the Prime Minister was standing along with various officials, with a rope barricade. We were advised to be patient and remain outside this Laxman Rekha. One senior local journalist, notorious for his irascibility, tried on a couple of occasions to breach the security ring, by either seeking to go from under or over the rope. In both instances, Special Protection Group (SPG) personnel gently pushed him away. He then began to complain loudly about the indignity that media people were being subjected to and warned that the country’s democratic set-up would not tolerate such high-handedness.

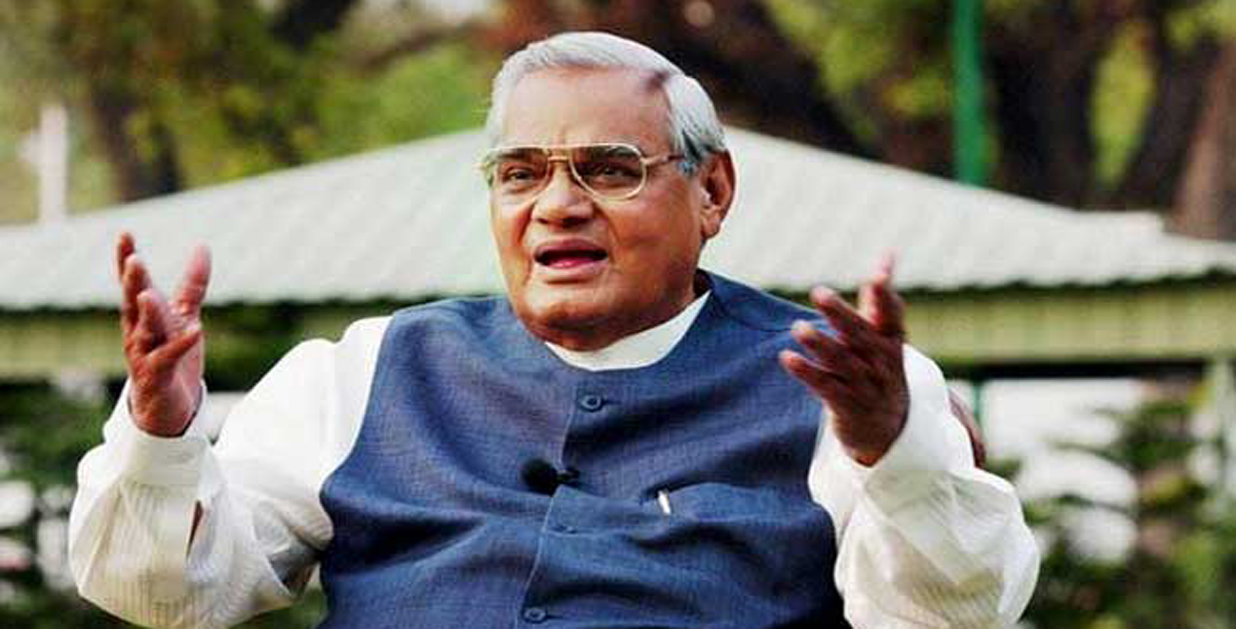

A hassled security staff member (from the SPG) came to me — for I was standing next to the agitated journalist and seeking to quieten him — and said he would be tempted to use force with the offensive man in case the latter made another attempt to break the cordon. The ruckus was loud enough to draw Vajpayee’s attention for a brief moment. He cast an amused glance in our direction and then busied himself with the people around him. Half an hour later, the ropes were lowered and we were allowed to approach him. He met us with his trademark dazzling smile. As I greeted him with folded hands, he said: “You people are lucky to be working in this beautiful State.” A day or two later, a DIP photographer captured him in an enigmatic profile: Seated at the beachside with a glass (in hand, or on the table laid before him, I cannot recall), as the Sun set on the last day of the year, a fierce red glow shooting across the sky. The image, splashed across the country, further added to Vajpayee’s aura.

Others had visited Goa before — Jawaharlal Nehru, who, baffled by the rejection of the people of the State of the Congress in the first election after the State was liberated from the Portuguese, had exclaimed that “Ajeeb hain Goa ke log” (strange are the people of Goa), Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi. But Vajpayee was somehow seen as being different — charming, gentlemanly, warm and witty; and attractive too! I cannot forget that he was treated like a superstar. He was that, in his own way. By then, Vajpayee had already established his credentials as Prime Minister with a difference. He had initiated long-term changes in the country’s creaking infrastructure (especially in the national highways and rural roads sectors), demonstrated the country’s nuclear capabilities with the Pokhran test (done so secretively that even the alert eyes and ears of the US missed it), extended a hand of friendship to Pakistan (through the Lahore-bound bus service), taught the Pakistanis a humiliating lesson when they went astray (in the Kargil conflict), yet again sought to recalibrate ties with Islamabad through the Agra Summit (an effort which failed due to then Pakistani leader Pervez Musharraf’s obstinacy), rolled out a politically-sensitive privatisation programme (which saw floundering public sector units being handed over to private management), and, without overtly disturbing the long-standing foreign policy contours of the country, deepened ties with the US and strengthened relations with Israel.

Enough has already been written in detail on how these bold and imaginative decisions enhanced the nation’s profile, both internally and globally, to need a repeat. But as tributes poured in after his death on August 16, some of those who were privileged to have worked with him, narrated Vajpayee’s commitment to the national good even at the cost of upsetting his colleagues. On the issue of revenue-sharing model — as against the licence fee system — for kick-starting a massive growth in mobile telephony, he backed his senior bureaucrat NK Singh (Singh wrote about the matter in an article for The Times of India, which was published a day after Vajpayee’s demise), who had pushed for the scheme and had opposed the then Minister for Telecommunications’ suggestion to invoke bank guarantees given by telecom operators to come out of the mess that the sector had landed itself in.

Vajpayee’s achievements as Prime Minister were stupendous without doubt, but he was at the helm for only a little over six years in all — before his full five-year term, he had been Prime Minister for 13 days and 13 months on two separate occasions. And yet, that brief period has been enough for people to evaluate him as among the best Prime Ministers the country has had; in a recent poll conducted by Mail Today, 94 per cent of the readers rated him as the best Prime Minister ever. This is nothing short of a miracle, given that Vajpayee was pitted against the likes of Nehru and Indira Gandhi, both of whom had longer tenures and thus greater occasions to leave a lasting legacy.

So, what made him the colossal figure that he became and will be remembered as, apart from his performance as Prime Minister? There are two aspects to his persona which contributed to the image. The first is his individuality: Poet, democrat, liberal. And the second is his political acumen: His singular contribution to the acceptability quotient of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) as a mainstream political party — not just among the masses but also other political outfits who became allies of the BJP, with quite a few of them continuing to be partners to this day. Let us not forget that Vajpayee was something of a national and international rock star even before he became Prime Minister, unlike some others who came to be known after heading governments. As a Minister in the Janata Party Government from 1977 till the regime collapsed under its own weight, he was a star performer for the country in a Cabinet that consisted of people who were busy settling petty scores. Before that, he had built a formidable reputation as a parliamentarian since the late 1950s, leading Nehru to reportedly comment that the young Vajpayee had it in him to some day become the Prime Minister.

Thereafter, he swiftly made his national presence felt by reshaping the BJP (with the help of other seniors, primarily his friend LK Advani who happily played a supporting role), making it the country’s single largest party in electoral numbers in the mid-1990s, and forming the first ever BJP-led Government at the Centre. In more ways than one, he laid the foundations for the massive victory the party notched in 2014. But well before he became the Prime Minister, he had won the hearts of the people by his conduct and his evocative poetry.

His accommodative nature notwithstanding, he never ceded ground when it came to the core principles on which his party was founded, and he was scathing in his criticism of his political opponents. His speech in the Lok Sabha in 1996, at the end of which he declared he was tendering his resignation as Prime Minister, remains a classic. Vajpayee had torn apart the opposition parties which had come together to deny him a majority in the House, saying that they had nothing in common but a determination to see his back, and pointing out that they had all fought against one another just weeks ago. Also, on more than one occasion, he had flaunted with pride his links to the RSS and his commitment to Hindutva, taking his rivals to task over their criticism. He even wrote a poem celebrating his Hindu-ness. Yet, his choice of words and the manner of his attacks were such that they left his rivals wounded but not hurt. He was as quick to reach out to his opponents when the need arose, thus blunting any resentment that they may have nurtured. Vajpayee was both politician and statesman. Add his poetry to that, and you have a romantic idealist too.

At heart he may have been a simpleton, but there were several layers to his persona. Peel one endearing one, and you would find another equally endearing one. Benjamin Franklin had once said: “It is a grand mistake to think of being great without goodness. And I pronounce it as certain that there was never a truly great man that was not at the same time truly virtuous.” Vajpayee was that great man.

(The writer is a senior political commentator and public affairs analyst)

Image Source: https://d1u4oo4rb13yy8.cloudfront.net/article/bojdjlgemp-1514269483.jpg

Post new comment